The terrible cycle of violence that is life and death on the planet Skaro

I am a pacifist now that all my enemies are dead

Thal General probably

The Doctor: First Doctor (William Hartnell)

The Companions: Susan (Carole Ann Ford), Barbara (Jacqueline Hill), Ian (William Russell)

The plot: The Doctor’s curiosity gets the best of him when he lands on a blasted world with a distant ruined city.

Written by: Terry Nation

First aired: 21/12/1963-01/02/1964

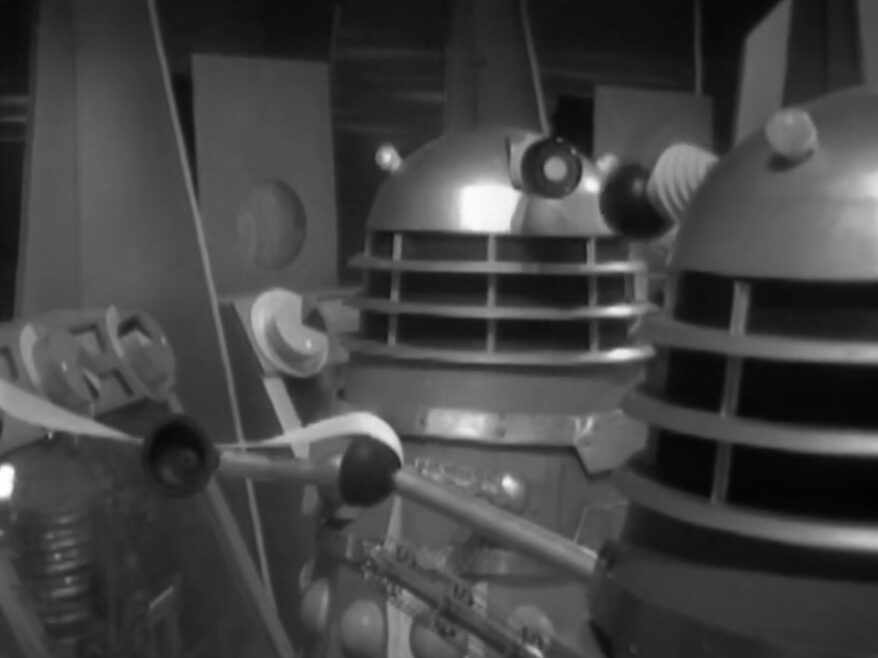

Continuity: First appearance of the Daleks

Season 1, episodes 5-11 review

There is a brilliant episode of Stargate SG-1 that has long been one of my favorites. In it, Earth is sent a distress signal by its ‘kindred’, a people called the Eurondans under siege by a powerful enemy. Cowering in their underground bunker and assailed by vicious, endless attacks from their ‘nemesis’, the group begs for help to survive the onslaught: food, medical supplies and heavy water to reinforce their shielding. They offer in return very advanced technology that Earth could use in its own defense.

While parts of the military are enthusiastic about helping, others on the mission have reservations. Why are they at war? What caused the conflict? And does it even matter under these circumstances?

What’s most interesting about The Other Side when compared to The Daleks is that, in the former, our team sides eventually not with the Eurondans but with their “nemesis”: the ones striking back against their original genocidal aggressor.

While both pieces end in an apparent Final Solution – and both are heavily influenced by World War II narratives – The Other Side sees the destruction of the Eurondans as something they brought upon themselves with their attempt at ethnic cleansing. In contrast, there is an interpretation of The Daleks whereby the Doctor and his companions help the Thals to complete finally the extermination of their enemies started so many centuries before. And all to ensure their own survival.

It’s an uncomfortable reading to say the least.

The Daleks was written at a time when the second world war had been over for nearly 20 years. Just long enough for wounds to heal but not long enough that scars had faded. The Cold War was raging (when The Daleks began airing, the Cuban Missile Crisis was only a year in the past). And in 1963, the Soviet Union, United States and Britain signed a treaty banning all but underground nuclear testing.

Cold War blocs, the looming threat of nuclear war and the shadow of World War II’s atrocities all influenced Nation’s acclaimed script. And, like the best of Classic Who, Nation’s story has no clear heroes nor any clear moral choices. It’s a tale of survival and the endless devastating cycle of violence that can stop a society from moving past its history.

It’s easy to be reductive when looking back on the introduction of the Daleks. Unlike later historical revisions, they are no screeching one-note, genetic-obsessed cliches. They are menacing and cunning and, from the viewpoint of our protagonists at least, amoral. But there is nothing in the script that suggests they are villains in some kind of objective sense. They are only the villains from the viewpoints of the characters we care about. And that is the most challenging part of what happens as the story unfolds.

The Daleks begins as the previous story left us: with the Doctor, Ian, Barbara and Susan bouncing quickly and without preparation from Stone Age Earth and landing somewhere new. Dirty, exhausted and hungry, the group are nonetheless drawn outside unaware that radiation is dangerously high.

They find a world petrified; plants and animals turned to stone and the soil nothing but ash. It’s a mystery that ignites the Doctor’s imagination, fueled further by the glimpse of a ruined city in the distance and the discovery of a completely metal animal, now deceased.

Ian and Barbara want to return home but are told it’s not possible. With not one but two unscheduled jumps in the rackety old TARDIS, the Doctor wasn’t able to do the proper calculations and is not sure even where they are.

When the Doctor insists on investigating the city, his companions rebel and force him back to the TARDIS, something he is clearly not happy about. “Don’t you ever think he deserves something to happen to him,” says Barbara, not entirely joking.

Back in the TARDIS, the group gets something to eat and plans to get some sleep. But the Doctor is clearly chafing under the TARDIS’ new-found democracy; being forced to bow to a majority when previously he was in charge. It leads him to make a decision that will no doubt haunt him forever: he sabotages his own ship and insists they need to go to the city to make repairs.

It’s a move suited to this original trickster character but also a move that speaks to his stubbornness and belief that he is above both the humans and any questioning of his decisions. This Doctor may be frail and elderly but he is also arrogant, capricious and not above leveraging his superior knowledge. And this single foible, this act of childish defiance, will not only imperil his own granddaughter and companions but himself.

Two other things are happening in the background while the Doctor is building up to his little trick. The first is that Barbara and Ian are beginning to feel unwell but put their headaches and tiredness down to what they’ve endured the past few days. The second is that Susan becomes convinced there’s someone else on this supposedly dead plant, a conviction that is proven right when they discover a silver case filled with phials of a liquid. It is sent back to the TARDIS so the Doctor can analyse it later and the group continues to the city.

The apparently deserted city is metallic and advanced and full of doors that can be opened with a wave of the hand. While the Doctor rests (he’s suddenly exhausted, the radiation sickness he doesn’t know he’s suffering from affecting him), Ian and Barbara separate to search for the mercury the Doctor supposedly needs to repair the TARDIS.

In the serial’s most terrifying sequence, Barbara wanders the silver corridors for a while before realising the doors are shutting behind her. As her anxiety grows, she is herded like a rat in a maze down corridors that slide and lock behind her until she’s completely trapped. The ambient music is amazing in this scene (and throughout every scene in the city), providing an unearthly, echoing and metallic background to the rising tension. It’s as though you can hear the sounds of emptiness and steel and the growing threat of someone coming.

Then, in one of the show’s most iconic images, she rears back in terror as she’s confronted with what looks like a giant plunger. It’s an extraordinary cliffhanger, one of the show’s best.

Despite their growing concern about Barbara, the Doctor, Ian and Susan find a lab and marvel at the advanced equipment. The Doctor once again demonstrates his unfortunate tendency to Social Darwinism: his underlying ontology that equates technology to intelligence and intelligence to superiority. It’s a philosophy that Ian, a man of the post-war 60s, takes natural issue with.

DOCTOR: They’re intelligent, anyway. Very intelligent.

The Doctor, demonstrating his greatest character flaw

IAN: Yes, but how do they use their intelligence? What form does it take?

DOCTOR: Oh, as if that matters. What these instruments tell us is that we’re in the midst of a very, very advanced civilised society.

Some of the equipment measures radiation and the group finally realise the danger they’re in. They need treatment for radiation sickness quite urgently and need to travel to get it. The Doctor admits there is nothing wrong with the fluid link that Ian has brought from the TARDIS to “fix” but it’s too late anyway. They’re soon captured by the Daleks and thrown into a cell with Barbara. Ian tries a bit of defiance and they use a blast of lasers to paralyse his legs. He’s out of action for now.

The creatures we don’t yet know as Daleks are curious about their prisoners, whom they assume are surface-dwelling Thals. They note that radiation levels are finally dropping but that these Thals seems to be suffering from radiation sickness. If the Thals can survive on the surface but these four are sick then does that mean they use a drug? Is that drug failing them? Is that why they’ve come to the city?

Our group of course are not Thals but it’s a piece of information the Daleks simply cannot process. Their universe consists of themselves and of the Thals. They look like Thals. Therefore they are Thals. Or, to be more precise, they are not Daleks.

The Doctor makes a deal with the Daleks to send one of the group to the TARDIS to get the phials they found in the hope it’s the treatment they need. Due to Barbara’s advancing illness and Ian’s paralysis, this ends up being Susan. And although I already find the character ear-bleedingly infuriating with her screeching, she does muster up the courage to go (admittedly with a lot of shrieking and crying).

On her way back, she runs into a Thal who looks like an Earth human: tall, handsome and blonde. His name is Alydon and he explains he left the drugs for them deliberately. He wonders if the Daleks want the drugs to heal them or themselves and gives her another box of them just in case.

The Daleks of course have no intention of curing their enemy’s radiation sickness. They have been trapped in their city since the Neutronic wars 500 years past and now want to reclaim the surface. They nonetheless turn a blind eye to Susan using the second box of phials to cure her friends. The group remarks on how much friendlier the Thals are to the Daleks.

BARBARA: Why do the Daleks think they’re mutations?

Susan, not at all judging by appearance

SUSAN: I don’t know. Judging by Alydon, they’re magnificent people.

Having been farming on their plateau for the last 500 years, the Thals’ crops have died and they have moved down towards the city in search of food. If they can’t find it, they will die. The Thals are essentially climate change refugees looking for food aid from the Daleks until they can find a new place to farm.

Peaceable farmers they may now be but the Thals were the soldiers in the bygone era. The Daleks were the teachers and philosophers. It doesn’t take much cognitive work to figure out precisely who started this war and which group had the treatment for radiation sickness before that war turned nuclear. At this point, the decision to portray the Thals as strapping Aryan archetypes is thrown into stark relief.

After 500 years of peace, the Thals are now farmers and pacifists who want to break bread with their enemy and share ideas in a mutually-beneficial culture of learning. After being blasted to atoms, herded into a giant bunker and enduring centuries of mutations, it is a dream the Daleks do not share.

It’s an important point that the Thals have believed themselves alone for the last 500 years. Their response to discovering that they are not is curiosity and a desire to connect. The Daleks, however, have known that the Thals survived and have obviously been watching them. Waiting for them to attack again. This seemingly small difference matters.

The Daleks trick Susan into luring the Thals into a trap with the promise of food and a future of cooperation. Realising the Daleks have no intention of helping the Thals, the group manage to escape by hijacking a Dalek and putting Ian in it. It’s the first instance of blinding a Dalek by putting something on its eyestalk (in this case mud).

The group do their best but are not fast enough to stop the Daleks from killing the Thal leader (although Ian waits for him to finish his inspiring monologue before warning him. In future, Ian, you might want to yell “It’s a trap!” even if you do interrupt his speech).

With the Thal leader dead, Alydon becomes leader and a debate begins as to the best course of action. The Thals are rendered somewhat impotent by their confusion. They have no comprehension of why the Daleks would attack them.

ALYDON: If only I knew why the Daleks hated us. If I knew that, I could alter our approach to them, perhaps.

The Daleks

IAN: Your leader, Temmosus, he appealed very sensibly to them. Any reasonable human beings would have responded to him. The Daleks didn’t. They obviously think and act and feel in an entirely different way. They just aren’t human.

GANATUS: Yes, but why destroy without any apparent thought or reason? That’s what I don’t understand.

IAN: Oh, there’s a reason. Explanation might be better. It’s stupid and ridiculous, but it’s the only one that fits.

ALYDON: What?

IAN: A dislike for the unlike.

ALYDON: I don’t follow you.

IAN: They’re afraid of you because you’re different from them. So whatever you do, it doesn’t matter.

Unlike The Other Side, which was set only a single generation after the original genocidal attack, The Doctor lands on Skaro centuries after the nuclear cataclysm the warlike Thals rained down upon the peaceful Dals. Which raises another question about how we interrogate a script like The Daleks: how far back do we look for context when judging a conflict?

Assessing the situation as it stands on Skaro, the Thals are peaceful and harmless and the Daleks violent and dangerous. The Daleks are contained in their city for now but Ian and Barbara know that eventually they will seek out the Thals and destroy them. That is simply who the Daleks have become. As for what the Thals have become: they say they would rather die than fight. It’s who they are.

We will not fight. There will be no more wars. Look at our planet. This was once a great world, full of ideas and art and invention. In one day it was destroyed. And you will never find one good reason why we should ever begin destroying everything again. I’m sorry.

Alydon

But as Barbara points out, it’s easy to be a pacifist when there’s nobody to fight “Are they pacifists, genuinely so,” she asks, “or is it a belief that’s become a reality because they’ve never had to prove it?”

Ian wonders if they should remind the Thals of who they used to be if it would encourage them to fight the Daleks but the group decides the point is moot. The conflict has little to do with them and they should leave the two warring factions to their own devices. Which is a fine plan, except the Daleks took the fluid link they need to fly the TARDIS.

Instantly, our group’s fate becomes dependent on the Thals fighting back against the Daleks. It’s probably the only way they’ll get into the city and get the TARDIS component back. And so that’s what they do – incite the Thals to launch an attack against the Daleks.

Back in the city, the Daleks have begun distribution of the anti-radiation drug they hope will allow them to finally leave their underground bunker and reclaim the city. They also review surveillance footage that shows their former prisoners have met up with the Thals.

“It is logical that together they will attack us,” the Daleks conclude. And, you know, they’re not wrong.

What’s also true is that this is a fight for survival for the Thals. The Daleks wilI find a way to destroy them. If they want to live, then they will have to fight. And so the cycle of violence and war continues.

They say the seeds of the next war are planted in the peace of the last. And this is a peace predicated on the Thal belief that they had eradicated their enemies completely. But like those in the United States who were horrified at the destruction of the nuclear weapon they used to end the War in the Pacific, the Thals also decided to never use such violence again. And that vow lasted only as long as they didn’t have an enemy to use such violence against.

Speaking of seeds planted in the last war: without the anti-radiation drugs available to the Thal the Daleks have evolved to survive in the environment they were handed – one of high levels of radiation. The drugs they hope will save them instead prove lethal. With background radiation dropping quickly, the Dales realise they must keep the surface irradiated if they want to survive.

If the Daleks’ mutations are caused by the Thals’ actions and it is now a binary choice between which of them can survive, who’s to say the Daleks are in the wrong? They are no longer adapted to their own planet.

Either way, the two groups are now completely opposed – each must kill the other to ensure their own continued existence.

The Thals and the Doctor’s companions break up into two groups. The first will infiltrate the city while the Doctor and Susan will sabotage the Daleks’ surveillance equipment so they won’t see them coming. The latter succeed but are captured. The Daleks prepare to spray radioactive materials into the atmosphere, a plan the Doctor finds abhorrent. It’s interesting that he seems to have discovered a moral position on a situation he has so far approached with detachment. He’s appalled by the plan.

Due to problems with some of the scripts for the first season, Terry Nation was asked to extend The Daleks by a full extra episode. It’s probably why we spend so much time on the journey to the city (and almost a whole episode of our group jumping over a chasm one by one in some subterranean tunnels). Nonetheless, they finally infiltrate the city, free the Doctor and Susan and engage the Daleks in the control room. Lots of Thals die but the Daleks’ power source gets destroyed in the battle and they are rendered harmless. Everything that was the Daleks’ is now the Thals’, including the food they so desperately needed and the technology to grow it.

It’s finished. The final war. Five hundred years of destruction end in this.

Alydon

“If only there’d been some other way,” says a Thal sadly.

But there wasn’t. Which is the greatest tragedy of all.

The fact that The Daleks, a full 60 years later, can still provoke such debate and such analysis is testament to the strength of the script’s fundamentals. Terry Nation clearly put a great deal of thought and effort into the construction of his narrative and the place of our invested outsiders who stumble into it.

The Daleks are the clear villains of the piece and yet we’re forced to ask ourselves why. Is it because they’re ugly? (In one scene, a clearly smitten Susan explains with starry eyes that the Thals are most definitely superior to the Daleks, while imagining their strapping Teutonic leader). Is it because they’re inhuman? (Ian clearly believes that ‘humanity’ is a moral concept rather than just a biological one). Or is it because they threaten the lead characters of our TV show?

After all, it’s not that the Daleks have to die so the Thals can live (although this statement is true). It’s that the Daleks have to die for our protagonists to live. And if that doesn’t raise uncomfortable questions for you, it certainly does for me. If the Daleks hadn’t taken a component needed to operate the TARDIS, then the Doctor and his friends would have high-tailed it out of there the second they could and it would be the Thals that were annihilated instead.

Who’s to say that the Daleks, after ridding themselves of their enemies would not also rediscover their past of philosophy and science?

And if we had cast our eyes back beyond 500 years, back further even than the neutronic war that started it all, would we also find the seeds of that conflict? And back even further? More seeds planted in more distant pasts? Has this cycle of violence ebbed and flowed across millennia until the technology finally existed to enable a final solution to it?

What isn’t clear in this clearly self-contained episode is how The Daleks fits in to the future continuity and mythology of Doctor Who. Did the Daleks somehow survive the Thals’ genocide? If so, has the Doctor just started the war between the Daleks and the Timelords that becomes such a core part of the show?

For now, ignoring the future role of the Doctor’s greatest future nemesis, The Daleks is a nuanced and complex story about how violence perpetrates itself. Victims become perpetrators and perpetrators again become victims. A terrible cycle that can only end in death.

One thought on “The Daleks: Doctor Who, S1 Serial 2”