If you could touch the alien sand and hear the cries of strange birds and watch them wheel in another sky, would that satisfy you?

The Doctor

The Doctor: First Doctor (William Hartnell)

The Companions: Susan (Carole Ann Ford), Barbara (Jacqueline Hill), Ian (William Russell)

The plot: Schoolteachers Barbara Wright and Ian Chesterton are concerned about an unusual student, Susan. They follow her to a junkyard one evening and into what looks like a police box. It’s actually a time machine, Susan is an alien and her grandfather – the mysterious Doctor – whisks them away on an adventure through space and time. It’s one that takes them completely out of their comfort zone and into a dangerous new world – the distant past.

Written by: Anthony Coburn (C. E. Webber wrote episode 1)

First aired: 23/11/1963-14/2/1963

Continuity: First appearance of The Doctor

First appearance of companion, Barbara

First appearance of companion, Ian

First appearance of companion, Susan

First appearance of the TARDIS

As a child of the 70s – or possibly more accurately the 80s – it’s not an overstatement to say that Doctor Who was an intrinsic part of my childhood. Nor that it is possibly an intrinsic part of everyone’s childhood – at least if you grew up in a country that took children’s content from the BBC.

From humble beginnings as an educational programme way back in 1963 to a nostalgic and sometimes mocking cultural reference to a rebooted hit in 2005, Doctor Who has permeated popular culture for almost 60 years. Even those who never really watched it nor cared for it still know it. More intimately than they would admit.

Between 2003 and 2006, in the lead up to the launch of the high-budget reboot and in commemoration of the show’s 40th Anniversary, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) replayed as many of the classic series as it had available. Four nights a week for three years, the network systemically worked its way through a large part of the back catalogue: from the sparse and enigmatic The Unearthly Child until the final episode of the underrated 26th Season, Survival. It then began to air the new version of the show, with its big stars and even bigger budget: a high-octane, CGI-enhanced show for the 21st century.

It was a tumultuous time for me. I had returned home from two year’s abroad, looking for a career change but uncertain as to what it would be. I had done a disastrous turn in PR, then temped as I struggled to pay my rent and find my place. I had eventually found a job I quite liked when the company was shut down and I was made redundant. I finally washed up, almost by accident, on the shore of my current employment in a different city and a different life. I was as far from where I imagined I would be as was possible.

It’s probably no surprise that during this time one of the few constancies in my life was Doctor Who. Through all those years – different houses, different jobs, different flatmates, different cities – I taped the episodes (yes on actual VHS tapes from my television) and often kept the ones I liked to watch and rewatch. At least until my old VHS tapes warped and I decided to switch to digital.

My childhood memories of the show were vague impressions rather than clear outlines. I knew I had watched it, understood the bones of the concept. But it was a deep cultural memory; not a distinct one of any individual story or idea.

Like the show itself, my viewing was a strange mix of old and new, of nostalgia and of freshness. I knew Doctor Who but could also discover it for the first time. I showed the tapes to my nieces, barely out of nappies, who devoured them with a passion and became lifelong fans. It became something we shared and something that remained unchanged while everything else changed.

Ironically for a story about grand adventures in space and time, Doctor Who was instead the predictable in my hectic world. And despite everything about the show that failed, it worked for me despite its messy and sprawling mistakes. A product of decades of clashing interpretations, creative reimaginings, fluctuating audience interest, budget cuts, and social changes, Doctor Who has almost no coherence but might be the most coherent story ever told.

Fifteen years later and in the depths of a lockdown in the mundanity of suburbia and the security of my longstanding career, it occurs to me to retrace my steps. To watch the series again from the beginning and to pen some thoughts on each episode. To embark on my own televisual adventure in space and time, this time for a sense of escapism and true nostalgia rather than constancy and discovery.

So I’m going to rewatch Doctor Who. Or at least I intend to – this is a giant undertaking, something that will take me several years if I keep at it.

What these reviews or recaps will look like it something I suspect will evolve. There will be episodes where I have little to say and other that may spark essays (when I get eventually to Curse of Fenric be warned….)

One thing this will be is a personal journey almost entirely for my own benefit. There are hundreds of recaps, reviews, analyses and dissections of every part of Doctor Who. It is that iconic and that longstanding and that beloved. Others will say it better and with more insight, more love and more constructive criticism. I doubt I will discover something new about Doctor Who.

But I could discover something new about it for me. After all, that’s what a rewatch is all about.

Season 1, episodes 1 to 4 review

This post covers the whole of the first serial of Doctor Who, even though it is very much a tale of two tales. The first, a pilot to introduce our characters and the show’s premise, and the second a time travel adventure into the distant past. The final three episodes are often referred to by their episode names to distinguish them from the very different first 20 minutes: The Cave of Skulls, The Forest of Fear, The Firemaker. Alternatively, the serial is sometimes called 100,000 BC.

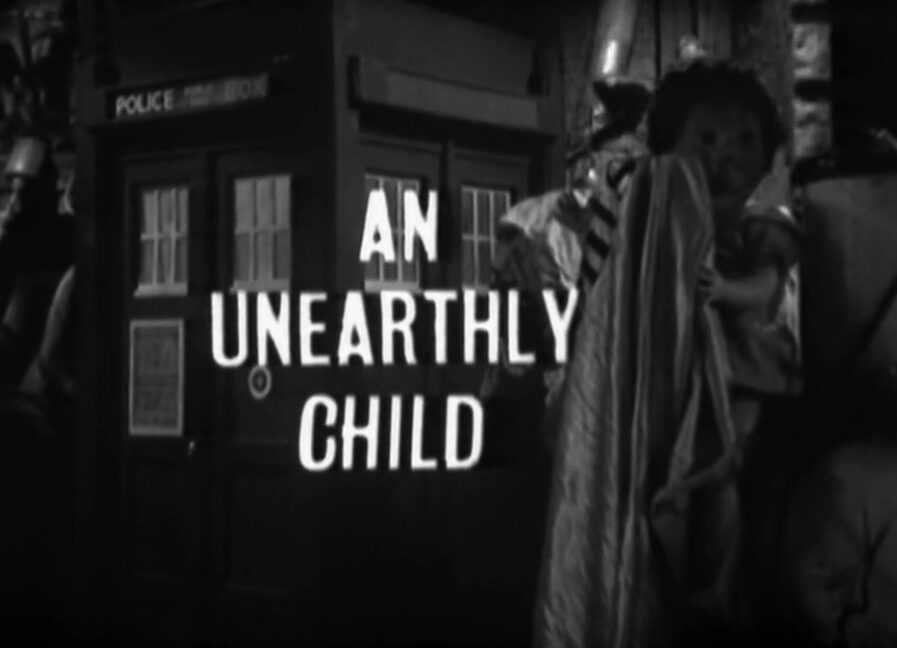

An Unearthly Child starts in the mundane and works its way slowly to the magical, using our future companions – Ian Chesterton (William Russell) and Barbara Wright (Jacqueline Hill) as ordinary and relatable characters that are then used to take us on the same journey.

Not just the mundane: the first episode starts in the grimy backstreets of London as we pan past a junkyard with a painted sign that says “I.M. Foreman, Scrap Merchant, 76 Totters Lane.” As the camera makes it way through the discarded detritus, the items deemed of no importance, it settles on a Police Box. And while this is an alien item to a modern viewer (especially an Antipodean one) at the time it would have been as unremarkable as everything else in that junkyard.

And so we have the show established in less than one minute of the first episode, testament to its fine writing. The magical is in the mundane. In the spaces where you don’t look. The things you deem unimportant. You just need to change how you view the world, change your perspective. Not everything is as you believe it to be.

Case in point is Susan Foreman (Carole Ann Ford): a student at the local Coal Hill School. Her science and history teachers, Ian and Barbara, are pondering the mystery of the 15-year-old: an apparent genius with vast knowledge far beyond her age but strange lapses in that knowledge and poor homework.

On rewatch, Ian and Barbara are obviously “stepping out”, as my grandmother would have it. She goes to him at the end of her day to discuss her problems, they workshop a solution and then embark upon it together. They have an easy, comfortable intimacy and she accepts a lift from him as though it’s a thing she does every day. Ian and Barbara did not eventually become a couple. They clearly already are.

Barbara’s problem on this day is Susan and her concern (and her curiosity) about the unusual teen’s home life with her grandfather that “doesn’t like strangers”. She wanted to speak to him about his granddaughter’s education but found the listed address was that junkyard at Totters Lane. Now she’s wondering what the girl is hiding and Ian easily agrees to help solve the mystery.

The unearthly Susan is currently being a very 1960s teen and dancing to popular music on the radio. Barbara lends her a book on the French Revolution (“What’s she going to do? Rewrite it?” quips Ian) and Susan insists she’ll have read it by the next day.

The song Susan is listening to is by a fictional band she calls John Smith and the Common Man. John Smith, Ian informs us, is the stage name of someone called the Honourable Aubrey Waites.

Whether deliberate or not, the show has delivered another pocketful of imagery: a peer pretending to be ordinary and rocking it out with the Common Man, all under the name of John Smith. Just as the Doctor does later when he repeatedly dons a persona of the same name.

After dropping off the book, Ian and Barbara stake out the junkyard while further discussing Susan’s idiosyncrasies and coming unerringly close to the conclusion that they’re just there out of curiosity rather than genuine concern for Susan’s wellbeing. Are they caring teachers who want to help a pupil or a merely busybodies with a mystery to solve? Possibly both.

Susan finally arrives at the junkyard and they follow her in only to discover she’s nowhere to be seen and there are no other exits. There’s only the Police Box – common and unremarkable but with no place in a junkyard. But, as Ian soon realises, humming as though it’s alive.

Ian and Barbara are just about to go and find a police officer when along comes Susan’s grandfather (William Hartnell). Susan yells out to him from the Police Box and her teachers assume he’s holding her hostage or is otherwise imprisoning her in the box. Hartnell’s Doctor is clearly playing with them at first. For all their altruistic sophistry, what they’ve been doing is tantamount to stalking. His sparkling eyes and impish smirk are those of a trickster or a charlatan who holds all the cards and is enjoying the farce of you thinking you’re playing the game.

His attitude changes when Ian and Barbara push past him and into the box. It’s a post-modern Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe moment or possibly and Alice in Wonderland descent into madness. Running after a white rabbit for the sake of curiosity and finding yourself upside down and the wrong size in an entirely different world. One that they’re not going to be able to leave with any ease.

Susan and her Grandfather, whom she refers to only as the Doctor, are alien time travellers in exile. The TARDIS is a ship that travels in time and space. Susan claims she named it the TARDIS for its initials – Time and Relative Dimension in Space – a piece of continuity that is short-lived when we later meet other members of their species.

What the Doctor does next is open to interpretation. He either panics that someone has discovered his secret and sets the TARDIS into flight with Ian and Barbara on board. Or not. It’s certainly curious that an alien intending to leave would care if two local schoolteachers know about him. Hindsight makes us wonder if he’s concerned about the Time Lords. But I wonder if he thinks it would be a lark to take this sceptical but curious pair on a jaunt through space and time to assert his own superiority over them.

Ian’s insistence that all this talk of time travel and moving Police Boxes is clear nonsense seems to annoy the Doctor a great deal, as is the implication that he may have indoctrinated his granddaughter into some sort of cult complete with delusional aspects of semi-Godhood.

“Your arrogance is nearly as great as your ignorance,” the Doctor remarks with a supercilious chuckle while refusing to let them leave. Ian accuses the Doctor of treating them like children, the Doctor retorts that children from his civilisation would find that an insult. Even children of his world know the mechanics of space and time.

Whether it’s fear or proof he’s a superior being, he sets the TARDIS into flight to land onto a barren wasteland. As the small blue box sits alone in the emptiness, a dark figure casts a menacing shadow that looms in its direction.

As the next episode opens, we’re plunged into a very different second story and find it is the shadow of some kind of Stone Age human. The next three episodes explore further the conflict set up in the pilot: one between societies at different level of technological development and how each respond to the other.

Stuck in a rapidly-approaching Ice Age and imprisoned by a local tribe of Stone Age humans, the group of modern humans and advanced aliens become embroiled in a power struggle caused by the death of the previous leader. Coming into this story once again, I pressed play with some trepidation, wondering if I was going to get a Great White Saviour Narrative or, possibly worse, a Noble Savage one. I was already side-eyeing the first episode’s reference to “Red Indians” and the possible implication that technology is a symbol of social progress.

Rather than being primitive, these Ice Age humans are portrayed as being human. Very human. The tribe killed their leader for discovering fire only to discover that life without it is much harder, especially as the cold closes in. The older members of the tribe fear the technological progress that fire represents – and the shift of power and authority away from them – while the younger generation desire it. It’s the timeless rejection of the new by the old and the embrace of it by the young. It’s a clash of cultures and generations that mirrors the clash between the Doctor and his granddaughter and between the time travelers and their new companions.

The tribe’s leader, Za, was never taught the secret of fire by his father, the Firemaker, and is slowly losing the support of the tribe because of it. The outsider, Kal, has seen the opportunity to seize power and is ready to exploit any cracks in Za’s leadership to do it. He sees the Doctor lighting a pipe with a match and takes him to use in his power struggle. The others follow only to be captured as well.

What strikes me when taking the first serial as a whole, is that it’s much better written than I remember but just as boring at times. With a full hour of screentime to fill and not a lot of plot, it fills it with our group being captured, escaping, recaptured and then escaping again. The script at its core is an examination of social responses to change but with Paleolithic Politics being about as interesting to a child viewer as the modern version, it’s been padded with a lot of running around.

Nonetheless, the story of the Stone Age meeting the Modern Age parallels the meeting between the Modern Age and the Advanced Aliens very well (at one stage Ian repeats his interaction with the Doctor by telling Za that everyone in his tribe knows how to make fire).

Possibly more interesting is the group’s response to Ka being attacked by some kind of beast. Despite Ian giving the Doctor a dressing down for his sometimes-callous behaviour, he and the Doctor are instantly united in their determination to ignore Ka’s injuries. It’s Barbara who insists on providing assistance and Barbara who has little time for his cultural superiority.

You treat everybody and everything as something less important than yourself!

Barbara

While the tribe is frequently referred to by the Doctor as “savages”, Za, Kal and more importantly Za’s girlfriend, Hur, are shown as well-adapted political operators: intelligent and open to new ideas. Instead of reinforcing the Doctor’s prejudices, the series is telling us instead that it’s a flaw.

For the Doctor himself, he’s an enigmatic and irascible character. He cares for his granddaughter a great deal and is clearly deeply effected by his exile. But he’s also driven by a strong belief that he is simply better: technologically and intellectually at least. He’s certainly cunning, using his wits at several points to turn the tide in the group’s favour. And he shows a possible propensity to violence, unnerving for people brought up on the character’s Technological Pacifism. Who he is, where he’s from, why he was on Earth and why he was smoking a pipe he lit with matches are mysteries so far unanswered.

Unfortunately, Za and Hur’s ability to synthesise new ideas ends up the undoing of our group of time travelers. They hand fire to Za in exchange for being set free but also introduce him to the concept of cooperation: that instead of one ruling over the group, the group would be stronger if they all worked and learned together. Za takes on board at least part of this philosophy and decides his tribe and his leadership would be better if this new tribe of firemakers joined it – whether they want to or not. They finally escape and arrive, dirty, exhausted and shellshocked, back to the TARDIS. As the tribe descends upon the box, they lift off and into a new adventure.

The first serial of Doctor Who is well written and conceived but not the most interesting. The Ice Age was an interesting way to show our companions taken completely out of their comfort zone while still being in a world that is familiar. Certainly an easier transition into the show than a brand new planet or lizard aliens. But apart from The Unearthly Child itself, it is somewhat underwhelming television. However it does establish the show’s premise and characters just in time for the groundbreaking, history-making story that was to follow it.

Sidenote 1: The TARDIS is stuck as a police box

When landing in Paleolithic ?England? (the show never establishes the where of our past timeline, nor even the when. Much of this is left to show notes and the plethora of writings around the show over the last half century), Susan remarks that the TARDIS is supposed to change and blend into its surroundings. The mechanism appears to be broken, which is why it remains a 1960s English Police Box.

Sidenote 2: The Doctor has problems steering the TARDIS

Whether because he took off in a hurry on two occasions or because the TARDIS was old and needed repair when he stole it, the Doctor doesn’t take Ian and Barbara home at the end of the episode but “somewhere” else. Somewhere with high radiation levels…

Such wonderfull comments Lee regarding my all time favourite show, despite my unhappiness with it in more recent years re the poor quality of the scripts.

At the end of day, I am five weeks older than the show itself. The original episode recounted by you above was deferred as it was due to air on the day that Robert F Kennedy was assassinated.

We do have VHS tapes of those classic episodes still in existence some 30 years ago when it was being repeated for the umpteenth time. Even now we are rewatching my favourite story which is from the Jon Pertwee era: Death to the Daleks. The concepts in this story have rarely been equaled since by other shows.

I think your recaps will do Doctor Who justice and I suspect you will see things differently during your rewatch. So many shows have been inspired by its existence (though many a show runner will never admit it).

I can still recall watching an Unearthly Child at a very young age. My parents often regaling in stories of how I used to hide behind a lounge chair whenever Doctor Who or Lost in Space came on. I even remember being upset when William Hartnell transformed into Patrick Troughton. There is no doubt that The Aztecs (perhaps my favourite Hartnell era Who) was the impetus for my life long association, and interest, with archaeology.

I have more books than you can poke a stick regarding the history of the show and An Adventure in Space and Time is always worth a rewatch on the origins of the show. I also have Peter Davison’s autograph from when he signed a book for me during a promotional tour at the height of his Doctor Who era. I also have figurines, daleks, a Tardis model or two and a number of artworks. I also hang out at the Doctor Who booth during Supernova convention is on in town too.

As I have said to our kids, I can tell you anything about “Classic Who,” but struggle to name characters or recount stories during the last five years of “New Who.” The Capaldi era was a wasted opportunity. Just for the record, I never liked K9, even though we do have one as a bauble for our Christmas Tree 😂

I look forward to you Who journey.

I enjoyed both our watch and your review.

I had never had the opportunity to watch the older episodes of Doctor Who (as I told you, latest Doctor I can remember is Tom Baker).

So, watching from that perspective, here I am, with a non friendly, grumpy and despising Doctor was a bit of a shock. He’s not playful, but angry, but as you said, maybe it’s because it’s his first time on Earth, he still feels superior to humans, he’s not still the Timelord who accepted what he did and his responsibility.

But back to the serial, I liked it a lot and can only wait to join you during this journey.

I don’t care how long it takes us. We can do this.