Korea’s new death game drama delivers a profound if somewhat muted critique of capitalism

Everyone is equal while they play this game. Here every player gets to play a fair game under the same conditions. These people suffered from inequality and discrimination out in the world and we’re giving them one last chance to fight fair and win.

The Front Man

It’s difficult at any point to know what to make of the new Netflix Original Squid Game.

The imagery is Japanese, the sensibility Korean. For those familiar with Japanese death game dramas, the pacing is wrong. For those familiar with Korean character pieces, the violence and surrealism is too pervasive. The first two episodes are like they’re taken from two different dramas, one from each country.

There’s certainly a question as to whether these two narrative traditions mesh: Japanese death games tend to be fast-paced, metaphorical and plot-based, Korean dramas are slow-paced character pieces that often lose their plot somewhere along their meandering way.

It’s at least one reason why parts of Squid Game can feel both too rushed and too slow at the same time. The games are deliberately and interestingly childlike, designed as they were by a man longing for the communal nostalgia of his youth. And yet watching players chip shapes out of honeycomb or get mowed down in a bloody game of Red Light, Green Light simply isn’t that compelling.

In a later episode, the drama devotes almost an entire hour to the characters talking while they play marbles. This episode was supposed to be an excruciating psychological game of wits but the only thing excruciating was watching it as it dragged on. And it was only one instance at which the show’s sudden detour into character study detracted from its pacing. At the same time, the show’s descent into graphic violence – and at one point, sex – feels often gratuitous. As players are mown down by machine guns or brain matter explodes on the floor, it’s supposed to be shocking but instead has little impact. It’s sterile and almost predictable; designed cynically to shock and therefore not shocking at all.

But despite its earlier issues of pacing and tone, once Squid Game starts to navigate its way to its ending, it remains brilliantly on point. And while you could mistakenly believe that that point is ultimately gross – rich people get their thrills from watching the poor struggle – it is far finer and more nuanced than that. Because, in the final estimation, Squid Game intelligently examines the modern capitalistic fantasy of choice, fairness and equality in a game that is nonetheless rigged.

Squid Game brings us into its world through the character of Seong Gi-hoon (Lee Jung-jae). Amiable enough, Gi-hoon is also an inveterate gambler and total loser – in the most literal meaning of the world. Laid off from his job several year’s previously, Gi-hoon’s marriage has failed and he lives with his overworked mother who we find out has been hiding severe diabetes.

As a character, Gi-hoon is neither sympathetic nor likeable. He steals money from his mother to gamble on the horses. His previous gambling has left him with mountains of debt and several angry creditors of the kneecapping persuasion. He seems unwilling to get a job and berates his mother for “working so hard” while stealing her debit card and draining her account. On the surface at least, Gi-hoon’s financial problems are not structural and watching him approach the world with a kind of lackadaisical entitlement does not help us connect with him as a person.

The same can be said of many of the other contestants we meet in the brutal playground that is the Squid Game, especially the former broker and SNU graduate, Cho Sang-woo (Park Hae-soo). Sang-woo has long been held up to Gi-hoon as the paragon of his neighbourhood, to which he has failed to measure up. On paper, Sang-woo has won the game called capitalism. Gi-hoon has stopped playing at all.

It’s no surprise that Sang-woo and Gi-hoon end up being the two players left standing at the end: one willing to do anything it takes to win the game and the other unsure if playing is the right thing to do at all. And yet Squid Game gives us other characters far more sympathetic whose lives – and deaths – demonstrate the alluring lie of our prosperity cult.

Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon) is a North Korean defector who came to the south to pursue the affluence she believed was waiting and Ali Abdul (Anupam Tripathi) is a Pakistani migrant also chasing Korea’s economic miracle for himself and his young family. Both are now thoroughly disabused of the romantic notions that brought them to this new promised land and are willing to gamble their own lives to help pull their loved ones out of a financial hole not of their own making.

As well as the requisite ratbags, murderers, gangsters and thieves that provide a menacing backdrop to the games, it is these characters that shine the most light on the show’s themes. These are two people who are never going to win, whether inside or outside the game. But for them, more even than our other contestants, playing isn’t really a choice even if it is portrayed as one.

And yet one of the underpinning premises of the drama is that the contestants have a choice. A choice to play. A choice to leave. A choice to live, to die. A choice to kill. After the first game – designed to be nothing more than a straightforward slaughter of individual players – the group votes to end the game and leave but are given the option to return. Of those who survive, the majority soon choose to come back.

Unlike other death game dramas, such as Alice in Borderlands, where characters are forced or tricked into playing, the contestants in Squid Game give informed consent to compete. Those who win are catapulted into the echelons of the super rich. Those who lose will die.

It’s a gamble: a brutal, horrific gamble that the players are staking with their lives. And yet, as we learn, the real stake is not their own bodies but the bodies of others. They are not gambling with their own lives but with their willingness to kill others. The path to this kind of money is strewn with atrocities: atrocities that are excused and accepted as long as they are within the arbitrary rules set down by the game masters.

It’s a game that’s ostensibly equal in that each has the same opportunities to win. But a game that’s inherently inequitable, played entirely within parameters set down by those with the power to set the rules of the game itself.

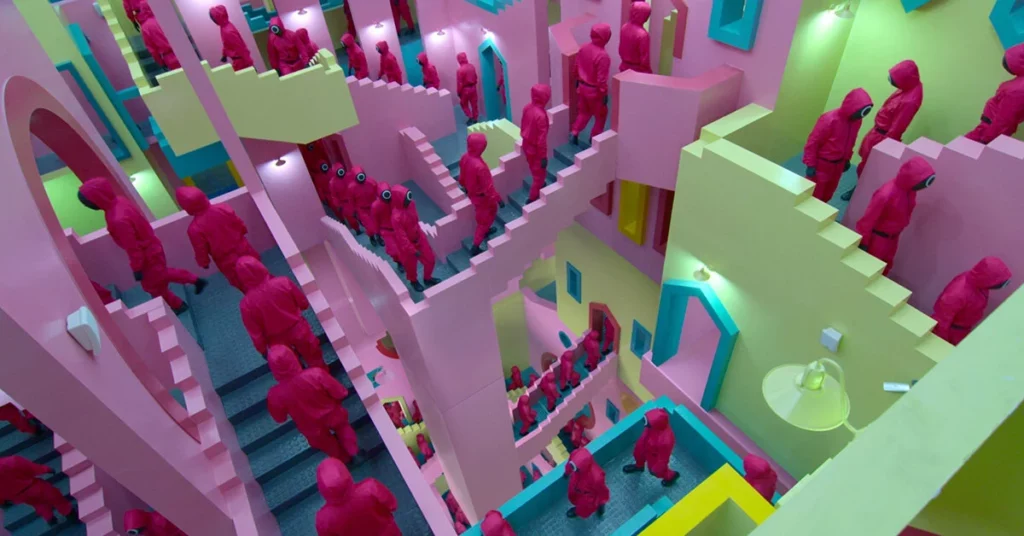

As our players stop being mowed down by the game and begin instead to tear each other apart, they are watched over by a clique of the already wealthy. Bored rich men who amuse themselves by watching those at the bottom fight it out to attain what they already have.

It’s a framing that puts the lie to the claim that this is equity. Everyone is treated the same under the rules of the game of capitalism. But true equity requires some input into the rules of the game itself. Great wealth awaits for those who are willing to give up any hint of empathy, consideration or humane treatment of others: those willing to leave the lives of others strewn around them as they move to the top. But for most of those who play, they will fall along the way or eventually drop out of the game completely.

And as Seong Gi-hoon finally graduates to being someone wealthy enough to set the rules of his own game, he’s forced to make the same decision: does he play or not play? Near the end, Gi-hoon joins the main game maker in his penthouse looking down on the game of life. They watch as a drunk lies freezing on the street and bet on whether somebody will help or walk on by. And while Gi-hoon is on the cusp of walking past the game that continues now that he is above it, he chooses instead to turn around and, finally, take some responsibility for his new status.

So if you choose to persist with the Squid Game through its ups and downs of pacing and tone, you’ll find it does have something to say. And while I wish that statement was a bit more blistering and a bit less muted, Squid Game is indeed a critique of capitalism and a surprisingly finely-tuned one at that. And perhaps, on reflection, leaving its meaning to the very end enables the script to take you on its journey without prejudice.

One thought on “Equality and Equity in Squid Game”