For Waadmay

The aching soundtrack of Human Disqualification speaks to the show’s longing for connection in a world where relationships are failing

There was a time you let me know

Hallelujah

What’s really going on below

But now you never show it to me, do you?

Remember when I moved in you

And the holy dove was moving too

And every single breath we drew was Hallelujah

A man ties his hands to another and drowns himself in a reservoir. As he sinks into the icy depths, he is inextricably bound to his companion. Even death, it seems, is not something humans want to face alone.

As Jeff Buckley’s Hallelujah echoes across the dulled endless night of the Korean drama Human Disqualification (alt. Lost), the song is both a source of imagery, inspiration and impetus to the characters who play it endlessly: deconstructing its lyrics for some vital clue into the mind of their friend who has killed himself.

Of course the music to this (almost exhausting )discussion of depression, sadness and general ennui is wider and broader than just the Jeff Buckley version of the Leonard Cohen classic. And yet the song permeates not just the soundtrack but the show’s themes, characters and imagery.

This post is not a review of the show Human Disqualification per se. Nor is it a compare and contrast with its supposed source text (Disqualified From Being Human by Osamu Dazai). Nor indeed is it the discussion of suicide ideation the drama possibly needs or a deep dive into the show’s arguable flaws. Instead it’s a simple discussion of a soundtrack I thought was a masterpiece.

That soundtrack of soulful strings and orchestral pining was underpinned by Hallelujah: a song the show tells us is about the biblical story of David and Bathsheba. In reality, the song mixes up several biblical references to sexual obsession; with David and Bathsheba being followed immediately by Samson and Delilah before moving into stanzas about loneliness and emptiness. A clear autobiographical reference to Cohen’s own life.

Your faith was strong but you needed proof

Hallelujah

You saw her bathing on the roof

Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew ya

She tied you to a kitchen chair

She broke your throne, and she cut your hair

And from your lips she drew the Hallelujah

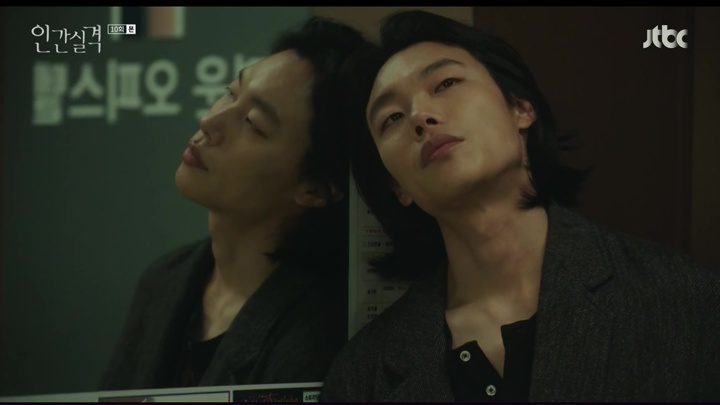

The show starts with suicide and the lure of death weaves itself through the text as it weaves its way into the psyche of especially our female lead, Lee Bu-jung. Previously suicidal, she used to be a member of an online suicide club – and possible cult – called Cafe Hallelujah. A club that uses Jeff Buckley as its avatar; a man who drowned, fully clothed, in an incident that has long been suspected as suicide. A man whose image strongly resembles Ryu Joon-yeol’s (playing Lee Kang-jae) styling in the drama.

The imagery of Hallelujah is used as a repeated motif throughout the drama. In homage perhaps to the song’s Samson allusions, the male lead, Lee Kang-jae, sports Byronic long hair that he eventually cuts in an attempt to put his desire for the female lead behind him. The characters sometimes identify themselves in imagined interpretations of the song. Kang-jae’s best friend, Ddak-yi and business partner, Kang Min-jung see immediately the David and Bathsheba parallels believing themselves to be in a love triangle (although who is David, who is Bathsheba and who is Uriah remain open and are unimportant anyway). The triangle is not about romance at all. Almost none of the relationships are.

If we meet again, do you want to die with me?

Lee Bu-Jung

And yet, while the show is ostensibly about sex and is haunted by the strains of a song about sex, it is strangely – or not so strangely – sexless. Our characters are so sad, so swamped by feelings of ennui, that they live their lives as if they are in a dense fog or fighting against turgid waters. It’s no surprise then that show has opted for Jeff Buckley’s version of Hallelujah.

Cohen’s original is raunchy and guttural and oozes sex. The chorus sounds like an ecstatic exclamation. It’s a song driven by lust and a desire to possess; an obsession that leads to destruction. In contrast, Buckley’s is the quiet sadness of a relationship that started in intense physicality and has withered away into silence and echoing sadness. It aches. It is indeed a cold and broken Hallelujah.

In fact, if it was possible to make a visual representation of this song, then Human Disqualification would be it.

As our characters walk mechanically and with dampened emotions through their days and endless sleepless nights, as they pace the floor of a familiar existence that nonetheless does not feel like home, they are like the walking dead contemplating dying. But not wanting to do it alone.

Well people I’ve been here before

I know this room and I’ve walked this floor

You see I used to live alone before I knew ya

And I’ve seen your flag on the marble arch

But listen love, love is not some kind of victory march, no

It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah

In the end, Human Disqualification’s conclusion that it is the ‘alone’ part that needs remedying in all instances, is one I take particular issue with. While the show grapples throughout with its representations of sadness – and as an audience at one point we’re also just floundering in their insubstantial sadness as much as they are – the show’s use of Hallelujah instead suggests the show is about loneliness and a desire for connection. A connection that we sometimes use sex as a shortcut for but one that can elude us nonetheless.

But while connection is indeed a human solution to the human problem of loneliness, it is not a cure for depression or its younger sister, persistent sadness. In this respect, Human Disqualification can be said to fail as much as it succeeds. Possibly because a narrative needs a conclusion but the life of sadness we lead does not and cannot have one.

Maybe there’s a God above

But, all I’ve ever learned from love

Was how to shoot somebody who outdrew you?

And it’s not a cry, that you hear at night

It’s not somebody, who’s seen the light

It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah

Thank you so much ❤️❤️❤️❤️

As you said I felt that the song is solely used in the drama to point the desire to be connected , understood and belonged to somewhere, someone or something .

“it is the ‘alone’ part that needs remedying in all instances, is one I take particular issue with.”

Me too. Being alone, wanting to be alone, is not a problem needing a solution. Sometimes, it IS the solution. Sometimes, it just is the season, and something to be enjoyed while one can.

There’s nothing wrong with being alone and that doesn’t need remedying at all , but depression and feeling lonesome is something most humans by nature try to remedy by seeking companionship of course some don’t.

‘but the life of sadness we lead does not and cannot have one.” I love this part so much.