Want to know whether you should watch Strong Girl Nam-soon? I focus in on writer Baek Mi-kyung; her history and idiosyncracies in a new series showcasing Korean drama writers.

Baek Mi-kyung is one of those writers who is possibly polarising or maybe just an acquired taste. Writer of the perennially popular, Strong Girl Do-bong Soon and its currently-airing sister show, Strong Girl Nam-soon, Baek Mi-kyung is known for wild genre mashups, random absurdity and one of the most popular ships in Dramaland history. The love for Bong Bong and Min Min from Strong Woman Do Bong-soon is unflagging; so much so they were given an adorable cameo in Nam-soon that delighted audiences.

But Writer Baek is also responsible for what is inarguably one of the worst dramas ever written – Melting Me Softly. So, with a new show airing, I thought it might be time to deep dive into this controversial – sorry, “acquired taste” – writer.

Genre confusion and absurdity

What genre was Melting Me Softly? All the genres! A sci-fantasy, family drama, OCN thriller and romcom (and that’s just its first 10 minutes), Melty is the prefect example of Baek Mi-kyung’s commitment to genre melange. She regularly mixes and matches genre elements, often switching between genres swiftly and without warning.

The brutal and deeply misogynistic criminal in Do Bong-soon was jarring enough when contrasted with the show’s bubblegum pop romance, but this genre frappe was at its worst in Melty where the randomness and lack of narrative grounding turned the show into a mess. Some viewers of Nam-soon were no doubt puzzled when the show switched from a fish-out-water romcom to Batman to a simplistic diatribe against drugs that involved dead junkies and enough shots of empty water bottles to rival Happiness. And then back again.

Nonetheless, Baek has a natural flair for absurdity and, when this absurdity lands, it makes her dramas loads of fun to watch. Do Bong-soon carrying Ahn Min-hyuk bride style while I Will Always Love You from The Bodyguard plays is a delightful scene, as is Nam-soon building a traditional Mongolian ger in the Han River park using leftover construction materials and Seoul’s ever-present political banners.

The mind that gave us PTSD (post-traumatic stress dolphin) – where a character had a trauma response to stuffed dolphins – is the kind of mind that can generate no end of the unexpected and often completely random. But absurdity is just that. A single moment of nonsense. It doesn’t constitute a story. And while I generally love absurdity, it doesn’t carry 16 episodes of television.

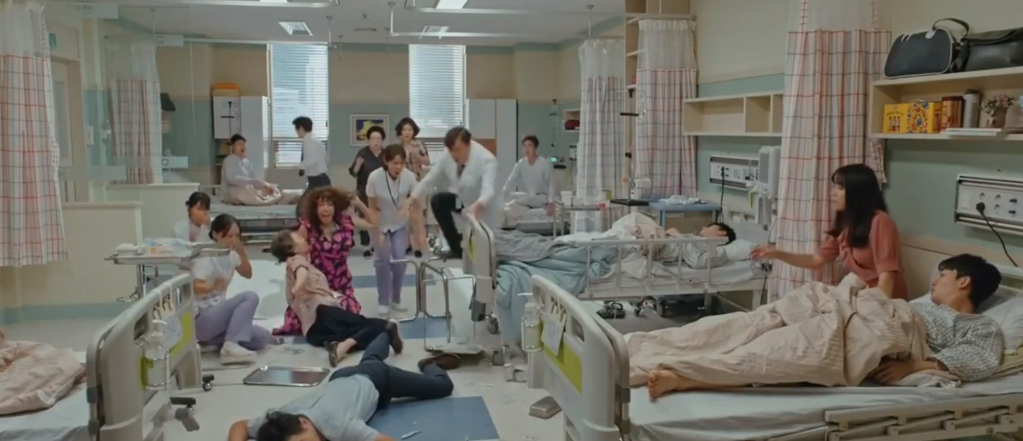

Slapstick and cartoon violence

“Koreans don’t understand my sense of humour,” bemoans Nam-soon’s Halmeoni, in what can only be a piece of meta commentary.

Baek’s pieces are full of slapstick and over the top violence, again played for humour. Of the three dramas I’m talking about here – Bong-soon, Nam-soon and Melty – all are to some extent comedic, even though, as previously mentioned, Baek tends to mush genres together like some kind of televisual bibimbap.

Having watched a few episodes of Nam-soon with an older relative, they found the show’s forays into physical humour to be hilarious, whereas slapstick as a general rule leaves me cold. And the Strong Girl series in particular has a violent element to the slapstick that some viewers don’t like.

And yet, as with her inversions and subversions (below), there is a cartoon element to the violence that suggests you’re not supposed to take it literally. Characters gets launched through the air, have their teeth knocked out in one punch, get their limbs dislocated and then wrenched back into shape. It’s Roadrunner violence; the only thing missing is an Acme label.

While humour is obviously subjective, if you don’t think violence is suddenly fine just because it’s cartoonish or, in the case of the Strong Girl series, because it’s a woman meting it out, then Baek’s works probably aren’t for you.

At this point, I’ll note that I’ve focussed in on the Strong Girl series and the tonally similar Melty. But Baek also wrote the Makjang drama, Mine and the body swapping, Miracle That We Met. These are both very different, although Baek’s love of Makjang is obvious in her three high-profile works as well. More importantly, in her analyses of power, she tends to think that if the world is run by bullies, well, it’s better to be one of the bullies than the alternative. Do Bong-soon may have fought against gangsters but she herself was also a gangster. One can only conclude that Baek doesn’t see the violence itself as a problem but who gets to use it.

Inversions and subversions

One of Baek’s characters in Melting Me Softly once complained that all of the stories are about princes riding horses and asked why we can’t have stories about horses riding princes. It is this line that provides the most insight into Baek’s dramas. Unlike other writers who subvert tropes for a dramatic purpose, for Baek the subversion is itself the point. She doesn’t subvert to teach or to convey a deeper meaning or social statement. She simply subverts for the sake of subversion. This, combined with her penchant for absurdity, means she loves to throw in random, inverted imagery for… fun basically.

Baek doesn’t subvert gender roles for feminism, for example, but simply gets enjoyment from throwing things in the air and seeing where they land. Often literally. In a world full of bullies, she thinks it would be fun to show those bullies being cute women or older women or other groups regularly seen as unthreatening. But they’re still bullies.

As a viewer, this can potentially be the most frustrating thing about watching her dramas. You expect the challenge to narrative or other conventions to have some kind of meaning. But for Baek, the challenge itself is the meaning. When Halmeoni uses her strength and wealth to throw a man she fancies over her shoulder and drag him into a hotel room, Baek wants you to laugh at an older woman doing something you would normally associate with a man. And that’s it. The fact that this behaviour is just as problematic in a man doesn’t worry her, nor is she expecting anybody to think about it too much.

“If a strong man can do it, a strong woman can do it too,” is not then her contention or thematic purpose but simply a modus operandi. Like Josh Whedon who wanted to show the young blonde victim in a horror movie fighting back and ended up an unexpected (and unworthy) feminist icon, Baek is simply turning images on their head for the sake of the inversion.

One of the things I found most frustrating about watching Do Bong-soon back in 2017 was that I kept searching for meaning in the show’s characterisation and often evocative imagery and finding myself later walking on empty air. If Min-hyuk puts the super cute Bong-soon into a dollhouse desk, does it mean anything? Or is it just fun, absurdist imagery? Across Baek’s filmography, it’s clear that it’s the latter.

As someone who loves absurdist imagery, Baek’s absurdism works for me most of the time – as does the enjoyable farcical nature of shows like Behind Your Touch. The issue then becomes how that absurdity is used. And this brings us to the main issue with Baek’s writing – and, tangentially that of Behind Your Touch as well. And that is she is always…

…Punching down

The problem with hierarchical bullying is that it’s not very tolerant of those who try to stand outside of the social system. Bullying being a tactic to keep the rebellious in line, especially in restrictive social systems.

Baek has an obsession with putting powerful authority figures, like male cops, into female dress; the humour of which classically comes from demeaning a man by associating him with the feminine. In this case, the humour comes from seeing someone ostensibly weak and sexualised be secretly powerful i.e. male.

Aside from the problematic side-swipe at men who may want to dress in clothes traditionally considered feminine – the latter scene from Nam-soon has the male lead’s colleague be patronising and disrespectful to him while he’s dressed as a woman – the repeated meme starts to tease out what’s wrong with Baek’s ostensible feminism.That is, that her concepts of power are around masculinity, money and physical strength and this inherent social structure is maintained regardless of whether certain powerful women have the right to respect within it.

This inevitably means that people who challenge that natural social order, such as gay, lesbian and other queer characters, end up the butt of many of Baek’s jokes. In fact, Baek, for all her apparent absurdist iconoclasm, is inherently conservative and ends up advocating a conservative type of feminism – that women have the right to the same respect as men so long as they embody male characteristics of strength while maintaining socially accepted codes of femininity.

Both Bong-soon and Nam-soon may be super strong and, eventually, super rich. But they’re also super cute. And while the juxtaposition is necessary for the subversion that Baek likes so much, it just ends up reinforcing the idea that women should adhere to external standards of femininity and men to classic external masculinity. Anything else is something to be made fun of.

Men who behave in an effeminate way, whether overtly or by being gay, are therefore portrayed as buffoons, perverts or just weak and useless. Strong Woman Do Bong-soon was notorious for its gay caricature; a truly offensive representation of a gay man in the workforce. But it also took a lot of its humour from the rumour that the male lead, Min-hyuk, was gay and must therefore dress as a woman and display predatory behaviour towards straight men.

In fact, Baek frequently punches down on just about anybody who challenges Korean social mores by being effeminate, gay, lazy, foreign, or having a drug or alcohol problem. And while there’s a whole ‘nother essay to be written about her ridiculous portrayal of illicit drugs in Nam-soon, her latest show is particularly bad for its treatment of a fat character.

Nam-soon’s twin brother, Nam-in, is portrayed as lazy and perpetually eating. As he devours entire plates of doughnuts or several servings of fried chicken, his weight is therefore seen as a simplistic product of over-eating. Overweight people on average eat less than normal weight people but Nam-in’s portrayal plays into caricatures of fat people as having self-control issues or being unmotivated. In fact, the fat jokes are unrelenting.

While humour is eternally subjective, I’d like to think we’ve progressed past humour that amounts to, “Isn’t it funny that this person is fat?” Or “Isn’t it weird how some men are gay?”

Baek’s tendency to punch down is probably the element that viewers will find most alienating about her dramas. Assuming they don’t enjoy humour at others’ expense. Which we all know some people still do.

Overall

No analysis of Baek would be complete without mentioning her romance plotlines. But while Do bong-soon (Park Bo-young) and Ahn Min-hyuk’s (Park Hyung-shik) is a super cute romance for the history books, Baek has never been able to replicate that magic. Her romance in Melting Me Softly between the frozen Ma Dong-chan (Ji Chang-wook) and Go Mi-ran (Won Jin-ah) was flat out skeevy and her romance between Gang Nam-soon (Lee Yoo-mi) and Gang Hee-sik (Ong Seong-wu), while sweet, is lacklustre in comparison with its predecessor.

Having said that, Baek seems to have learned from some of the critique of her 2017 hit and toned down some of Do Bong-soon’s more problematic elements. Her obsession with gangsters, for example, didn’t make this piece because it’s an element that Nam-soon thankfully seems to have shed. There’s a lot less gay shock and making fun of queer characters. Although with the addition of the strident fat shaming, it seems Baek has simply switched the butt of her jokes.

All criticism aside, Baek’s use of absurdity frequently makes her dramas loads of fun. And as long as you don’t make the mistake of thinking her subverted tropes and inverted imagery mean anything then her dramas are very enjoyable to watch.

But she needs to stop punching down.

When I watched Strong Girl Do-bong Soon it was very early days in my K-drama journey. I recall being cringed over the explicit violence, the poop wine and the gay baiting. My co-worker said her 13 year-old nephew loved the show and I realized that the level of humor was perfect for teen boys.

I’ve never done a re-watch but there are scenes I can recall vividly because they made me laugh, yet they were not the slapstick or pretend drag scenes. I can still smile over the FL asking about menstruation leave in her job interview. Now I realize that is just another example of the writer turning a highly codified situation on its head.

Lee, you icon you. That comparison with Joss Whedon was so incredibly on point. I’ve struggled so hard to find meaning in her subversions and failed so miserably, but I needed your lucid reasoning to lay it out for me conclusively. 😅 Thank you for freeing me from trying figure her out.