Before You Embark On A Journey Of Revenge, Dig Two Graves

Confucius maybe, James Bond definitely

As I sit at home in my recliner with the sunset smearing pinks and blues upon the sky and a warm cup of tea in a pink and blue mug in my hand and with Call It Love‘s intense minimalism on my television in, well, pink and blue, I start to ponder the meaning. Of pink and blue.

Why is this show so pink? Because it’s not just pink, it’s pink. My whole screen is a haze of pink hanging oppressively over characters like a miasma of washed out reddish tones. At points the pink merges into a kind of pastel blue forming shadows that characters walk into and out of.

Light breaks through in various points but never pierces the pink, which washes out the screen in a wave of algal bloom that meets with a blue like an ocean on a hot day. It’s not a happy tinge nor rose-coloured optimism nor any of the carefree associations with paler shades of red. Instead the pink weighs down on our characters as though it’s a miasma they’re forced to trudge through.

Pink is the traditional colour of love, blue the colour of melancholy or depression: the shape of water overwhelming us like a wave of emotion. But there are unfortunate (and painfully persistent) associations with gender as well. And yet the pink is not bold but vague; almost lingering. Pale pink. Light pink. Baby pink. Orchid pink. I google pinks.

The pink is not Hot Pink but almost cold or at least merely warm. Not as cold however as the light, pale blue. It hangs over the screen and the characters and the sets. In the air. Oppressive. If you could smell this television show, would it smell slightly off like a whiff of smoke in the air? A fine dust of earth and pollution. A miasma I said. A haze, I said.

Haze, Mirriam Webster informs me, is fine dust, smoke, or light vapor causing lack of transparency in the air: unclearness of mind or perception. If there is a haze of something, Collins continues, you cannot see clearly through it. If someone is in a haze, they are not thinking clearly or not really noticing what is happening around them.

The meaning of the show’s pink wash eludes me. Red and blue are two of the primary colours, standing in stark opposition to each other and pink is just a tint of red after all. Is the pink just there to highlight the blue? To stand in contrast to it? Is it in opposition to the blue? Or complementary to it?

So many questions, all vague and as misty as the show’s filter itself.

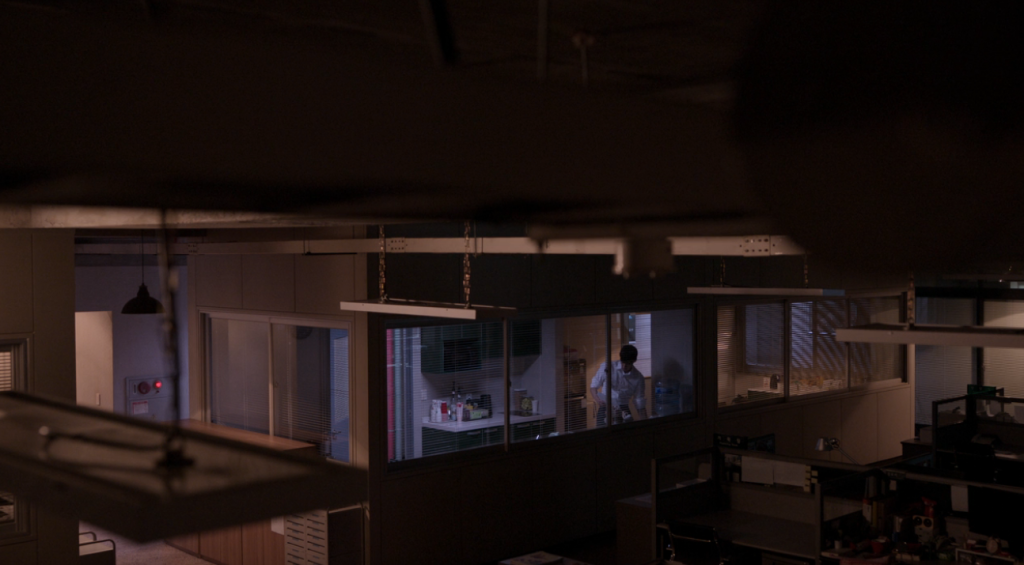

Our two deeply unhappy characters – one angry, one lonely – move around each other in the confined space of the show’s boxed in architectural cinematography. The set design is industrial, geometrical and full of deliberate shadows. Angular lines, exposed pipes and dark shadows in pink relief. It’s crowded but somehow minimalist like Art Deco.

In a way, it’s almost like a boxed assembly set of prefabricated furniture with a wash of faded pink. But at many points it’s beautiful. Truly beautiful. Achingly beautiful.

They say a poet once said the following. That if you want to understand, forgive and love someone, observe how they look from the back for a long time. That if you do just that, you wouldn’t have to unnecessarily try to understand, forgive and love them because their lonely shadow would have made you cry without you even knowing. They’re right. To understand someone’s loneliness: for me I think that’s the beginning of love.

Call It Love opening monologue

Regardless of anything else, Call It Love’s opening shot is a masterpiece.

A man walks from a gloomy room into an office bathed in the light of early morning or maybe late afternoon. That time of day when the sun doesn’t hit the world in its full force but diffracts and bends into pinks and blues and delicate oranges.

Other people move through those cubical, geometrical spaces until the camera finally pans out to a blocky, windowed office building and then to a city of office buildings. Small rectangular rooms in larger rectangular buildings bound by rectangular windows light up as the camera pans out: more and more. Until, from sufficient distance, it’s just a sea of twinkling lights.

And then still further out and through the frame of a poster, a picture, a framed and contained representation of Seoul. An image in a gloomy hallway in another sea of gloomy cubicles in another office building. A man walks through those blue-tinged halls into rooms framed with windows but this time he does not walk into the light.

Yet.

A box within a box, a story within a story. But a tale told as we pull out from our characters so their moods and vicissitudes become brightness at a distance. Beauty when seen from afar.

The twinkling lights of that poster are sprinkled lightly throughout the background at various point in the drama reminding us of that original framed Seoul that started this tale. Are we inside the poster looking out? Or, as an audience looking at a TV screen, outside that frame looking in.

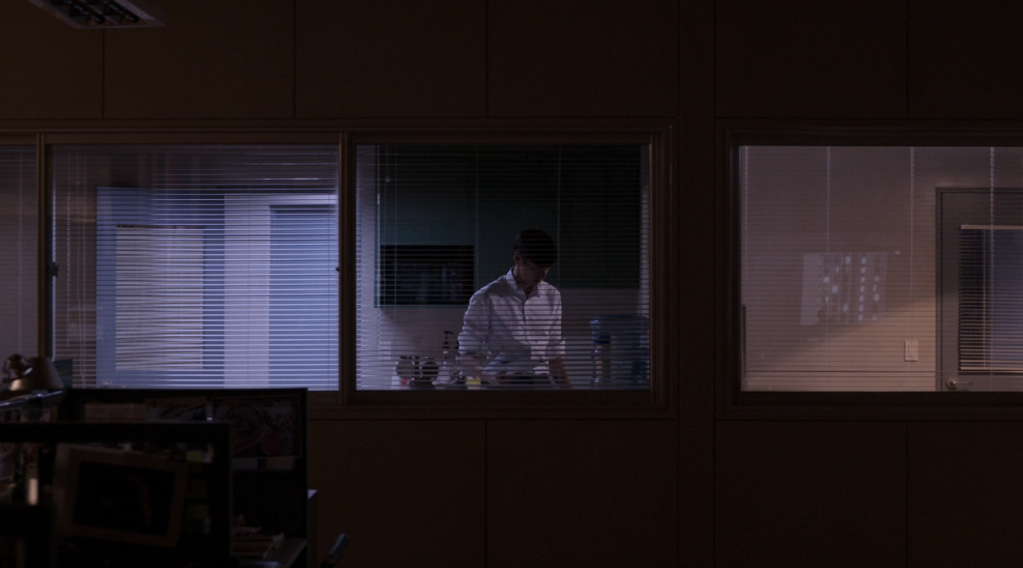

The camera in Call It Love is almost a disinterested observer: filming our characters unobtrusively from a place of detachment. Our male lead in particular, is shot from behind, through glass, as a reflection of himself and as a shadow on the world. We, like the female lead, see him only as a large, hunched back with deflated shoulders and a loneliness so permanently settled it causes his neck to bow under its weight.

Long dark reflections of himself stretch out in front of him, meaning he’s walking into shadow even when there’s a shaft of light. His loneliness is made palpable by the shadows forming between the pink and the blue where he either resides or then walks into. Either that or he is filmed as a small component of a larger world; dwarfed by the emptiness of a surrounding room.

Han Dong-jin is lonely but Han Dong-jin is also passive. He sits still in the world, even if he’s moving. Literally boxed in by window frames, doors, hallways, and geometric shapes.

Our female lead in comparison trudges through the pink filter like it’s a barrier she forces to give way to her presence. Her every act is an act of defiance. Even walking. And yet her actions are grimly, joylessly determined. She acts simply because she feels she must act. With determination but sometimes little thought in the hope that an action will made her feel less helpless, less hopeless, less impotent. A lashing out as she wants to hurt those who hurt her but, as we slowly discover, only ends up hurting herself.

While Dong-jin sites in gloomy shadow, Sim Woo-joo is wading endlessly against the stifling pinkness. Moving with determination simply for the act of moving. She is filmed constantly in robotic motion, in a slog of joyless movement: her loose comfortable clothing in dark greys and faded whites hanging off her skinny frame And, like Lee Ji-an from My Ajusshi (to which this show has obvious callbacks), always observing Don-jin from behind.

The differences between two people who, on the surface, are united in their mutual unhappiness is made stark in the conversation between the two when Woo-joo wrests him from the zebra crossing where he is nearly hit by a car. Instead of walking around miserable, she urges him to do something. Get revenge in some small way. Destroy them. Dong-jin retorts that the only thing that would achieve would be to make him feel bad about the horrible thing he’d done.

Revenge… It’s more like digging your own grave

Dong-jin

The idea that it is self-defeating to lash out at somebody who hurt you in the hopes they will feel your pain is a theme the show starts to slowly tease out as its progresses. Woo-joo – who once threw herself on the windscreen of her father’s car in the hopes that her physical injuries would help him to understand her pain – lashes out repeatedly at those who have wronged her but only ever hurts herself.

It’s a theme that’s repeated with Dong-jin’s other nemesis who becomes so boxed in by his own actions that he is left with only one path to take towards destruction.

And yet, through repeated imagery of Woo-joo’s enclosed loneliness representing his own repressed inaction, we see that his way is not the way either.

The show has an obvious sunset patina in its colour pallet and of course there’s an emotional component to the pink – its title includes the word ‘love’ after all. But if we consider the tension between lashing out and doing nothing: is it perhaps that the interaction between the red and the blue is the meeting place between action and inaction?

Blue is cold, is water, is depression. It’s molecules at rest. Red is heat, steam, fury. It’s molecules in motion. The contrast between our two leads is therefore not just anger and loneliness but movement and stillness. One vibrates in fury, the other at rest stays at rest.

Other characters wear pink: active characters willing to make moves and dent the world around them – for better or for worse.

On one hand therefore we have chaos: action without thought of consequence. On the other, we have inertia: the complete lack of motion. A function of the movement of human particles in the physics of a human world.

In the end though – beyond and above a somewhat self-indulgent deep dive into the meaning of a show’s symbology – ultimately the sum total of a drama becomes about what works to tell a story and evoke an emotion. Colours, lighting, sets, actors, scripts, and of course that persistent filter, will only work if they don’t become too intrusive. Good directing, good editing, even good acting are only good if you don’t notice them.

And while Call It Love is beautiful and often powerful in its subtlety, the pink sometimes becomes too pervasive. While it’s frequently used well, it is often just too obvious.

Why is this show so pink? sparked this post because sometimes, despite everything else the show is doing and doing well, it is overwhelmed by this unending oppressive, noticeable pinkness.

The screenwriter and directors are relative rookies. So if this is an example of their early work, in all of its flawed experimentalism, then we can look forward to great things in the future…

…don’t ask me about the flashback aspect ratio…

Call It Love is available for Australian viewers with full English subtitles on Disney+

Loved this piece, LT! I feel like the scriptwriter’s brief was “My Ajusshi but with romance”.

Those repeated call backs to “the back”, starting from ep1, are terrific.

I love how “the back” has become a character in itself, at least for me, not just because I keep looking at it, but also because the camera keeps showing it to us, over the episodes, how it has progressively grown – much like what you would expect of a human character. Such an original device – at once tells us something about everyone, the observer and the observed, and conveys so much in one movement – loneliness, tragedy, anger, anxiety, romance, happiness, contentment – oof, I put this down to excellent writing, directing and camerawork.