The seeds of the Little War were planted in a restless summer during the mid-1960s, with sit-ins and student demonstrations as youth tested its strength.

Logan’s Run, 1967

By the early 1970s over 75 per cent of the people living on earth were under twenty-one years of age. The population continued to climb – and with it the youth percentage.

In the 1980s the figure was 79.7 per cent.

In the 1990s, 82.4 per cent.

In the year 2000 – critical mass.

Like all my recent forays into classic science fiction, this one was sparked by the not-so-profound act of Netflix purchasing it and push marketing it to me. It’s almost like its algorithm knows me or something.

Unlike other science fiction film classics Netflix has acquired – 12 Monkeys, Dark City and Snowpiercer – I’m fuzzy as to whether I’ve seen Logan’s Run before. It’s in the same mental space as the original (and far superior) Blade Runner. I feel like I must have seen it in the dim mist of my past but can’t say for sure when.

Because of this, pressing play on the 1976 film felt like pressing play for the first time. Watching a film like this unburdened by any youthful nostalgia is why I felt it merited a blog post (unlike my recent rewatch of 12 Monkeys, which mostly elicited incoherent exclamations about this being “just as amazing as I remember, OMG this is so good, this is awesome”. Heartfelt maybe but not entirely blog material). Forget my 532nd watch of Dark City, which has been one of my favourite films for the last 20 years along with Donnie Darko.

Logan’s Run is based on the 1967 novel of the same name and is a dystopian tale of a future society practicing ritualised population control by killing everyone who reaches the age of 30. The domed city they live in is run by an advanced AI and split into two clear classes: those who exclusively pursue pleasure and those who ensure that nobody runs from their eventual fate. The latter are called Sandmen (a name that makes far more sense in the book than it does in the film). The concept has clear parallels to Huxley’s Brave New World, most especially in its use of drugs and sex to dull the population, its widespread sexual promiscuity disconnected from procreation (undertaken presumably by artificial insemination of a mechanical womb), and a sanitised view of death and social aversion to grief.

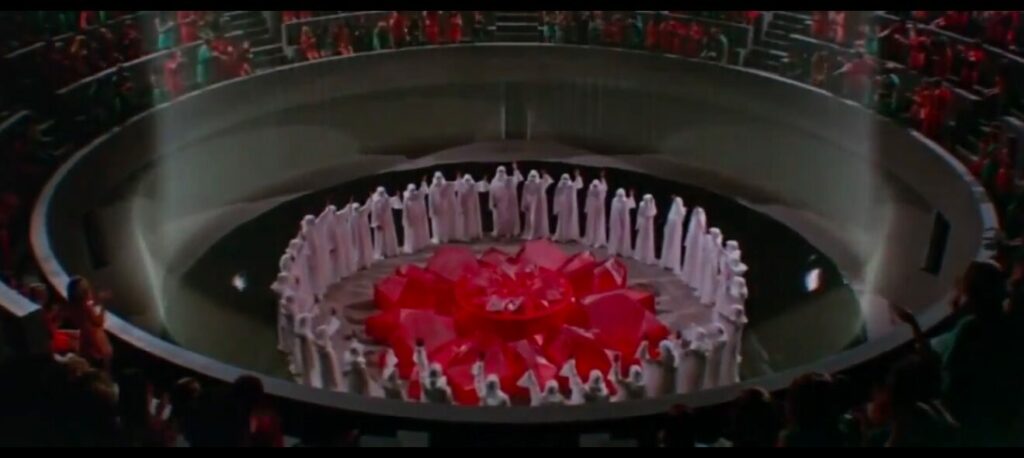

In the book, the citizens are sent to Deep Sleep in a Sleepshop at 21 and the Sandmen enforce it. In the film, the citizens are sent to the Carrousel at 30 and their deaths are somewhat of a spectator sport fueled by the promise of ‘renewal’ – a promise that is unsurprisingly empty.

Each citizen of the Dome has a crystal embedded in their hand that paces out their life cycle: Yellow, Green, Red, Blinking (a signal that you need to report for Carrousel) and then Black for death. Logan is a red with four years left before his Last Day.

Our knowledge of the catastrophe in the outside world is as limited as it is for the inhabitants of the Dome (although the opening quote helpfully positions us in the 23rd century and speaks of ‘war, overpopulation and pollution’). Given the incredibly short generations and the lack of societal memory, it could be 100 years or 1000. There could be thriving human civilisations outside its walls or nothing at all. In fact, to denizens of the Dome, the statement “outside the walls” is a meaningless and existentially terrifying one. To them, the Dome is the totality of their known universe.

Most interestingly, this is the case also for the AI that runs their lives. Its program is constrained entirely by the parameters of keeping the Dome functioning. No more, no less. As the film unfolds, we come to realise that it is as ignorant of the outside world as our main characters, knowing only what it must to keep its citizenry in line so the population remains sustainable.

Logan 5, our quintessential square-jawed, melanin-deprived male lead, is a 26 year old Sandman utterly socialised into the world in which he was born but with a tendency towards curiosity that his friend and colleague, Francis 7, remarks upon early. It’s not the deep seated emptiness of the male lead in the book but rather an affable questioning that doesn’t stop him from executing his duty as a Sandman. Logan also has a deep and abiding belief in Renewal, one that makes him wonder why people would run at all.

When Logan takes an Ankh off a dead Runner, the AI informs him it is a symbol of Sanctuary and is worn by members of an underground movement that helps Runners leave the Dome. The AI accelerates his life clock to Last Day and sends him on a secret mission to find Sanctuary. It’s a mission for which he approaches Jessica, a Green whom he has seen wearing an Ankh necklace. He convinces her he is serious about Running and, despite the scepticism of everyone involved in the underground that a Sandman would ever run, he finds the path out of the city with her help.

Narratively, this is by far the film’s most powerful section. To send him on his mission, the AI unwittingly destroys every aspect of the faith that has kept Logan a loyal servant of the system. It takes four years off his life without the slightest hint he’ll receive them back. It tells him that over 1000 would-be Runners are unaccounted for. It tells him that there is something ‘outside’, something beyond his known universe. And it tells him there has never been a single renewal. Logan is now facing death in all its stark absolute nothingness. The complete annihilation of self. And far sooner than he thought he would.

Is Logan running because he’s been told to? Is he lying to and manipulating Jessica? Or is he using this mission to secretly run for real. Either way, his behaviour is not unnoticed by the ideologue Francis who goes after him to try to bring him back, dead or alive.

One of the film’s more interesting diversions is when Jessica follows Logan as he pursues a Runner into Cathedral: an area populated by the Cubs. There are the Dome’s violent genetic mistakes: juvenile offenders who police a rigidly pre-adolescent gang-like culture, attacking outsiders and murdering any of their number who reach maturity. It’s not only a violent Dark Mirror for the hedonistic, drug-dazed culture of the Dome; it’s heavily implied that those sent to the Cathedral are genetic mistakes due to their unacceptable levels of intelligence.

Logan’s Run aesthetic is both very dated with its use of wires and models (the Carrousel scene looks like something from an interpretative dance troupe, the internal scenes of the Dome look like a train set) and yet somehow timeless. This is mostly due to how emotionally and intellectually sterile the society is, with its citizens going through the motions of eternal pleasure-seeking while machines do all their work and nobody thinks to ask any questions about how anything works.

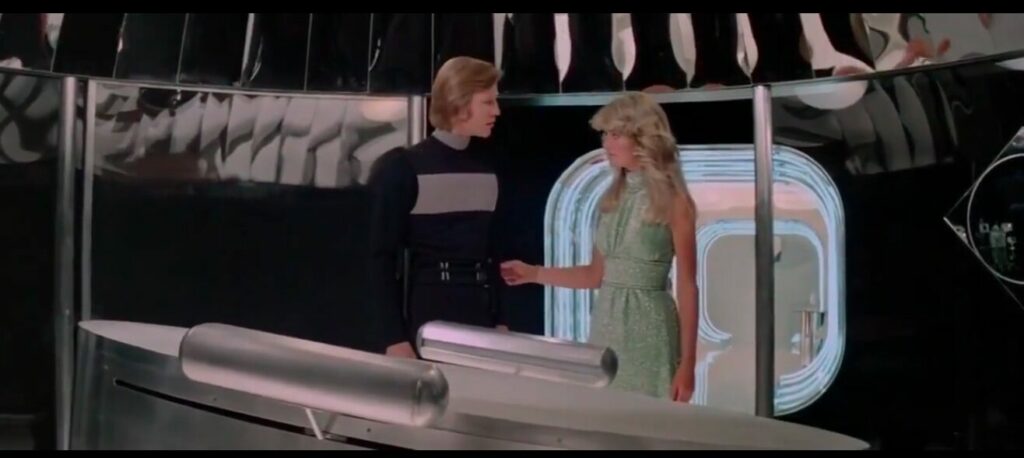

The casual nakedness of 70s cinema works well with the film’s themes and while its hair, costuming and makeup is very 70s – I’d make a joke about Farah Fawcett hair but since she has a minor part, it would be redundant – it embodies the perfect mix of glossy and antiseptic. Logan’s Run might be dated in its production but to a modern viewer this doesn’t detract from its portrayal of a future dystopia but rather adds to it.

Logan and Jessica make it outside the Dome only to discover that all the successful Runners did not make it to Sanctuary but were instead killed by a malfunctioning food robot. Sanctuary is as big a lie as Renewal was and at this point of the film I was as disquieted by the revelation as our main characters were. The Dome may be a charnel house designed merely for the perpetuation of the species, but there is no leaving. There’s nothing out there to run to.

Nonetheless, Logan and Jessica do some frolicking once they realise that the chips embedded in their hands have gone clear. Outside of the Dome and away from the AI, their lives are no longer constrained by an arbitrary end date and they’re free, apparently, to fall madly in love. It’s mildly improbable and extremely rushed but Jessica in particular has been dissatisfied with the Dome’s way of life for a while and seems ready to opt for lifelong monogamy. They keep pushing on hoping to find Sanctuary but stumble only upon the remains of Washington D.C.

The only human they find is a doddering old man who’s caring for an entire herd of cats in the crumbling ruins of the former civilisation. He’s vague and confused but tells them about being raised by his parents (who were in a committed relationship) between randomly quoting T.S. Elliot. The latter is so delightfully random it may be my favourite part of the film. Especially since our two Domers have never read a piece of literature in their lives and naturally think his bizarre rhyming responses are supposed to be answers to their questions.

Jessica and Logan decide to bring the old man – the only one they’ve ever seen – back to the Dome to liberate the denizens from their oppression. During the journey, Jessica realises that she wants to only be with Logan for the rest of her life and raise children together like the old man’s parents did.

Jessica and Logan’s return to the Dome with information about the outside world causes their society to collapse. With a combination of a logic glitch and a bit of well-placed gunfire, the AI explodes causing everyone to exit the Dome. It’s a little silly but achieves its purpose. The film ends with the Dome destroyed and a group of the world’s most useless humans thrown into a wilderness they have no way of surviving.

As a film, Logan’s Run works very well, although the psychological study of how Logan came to run is far more interesting than the Blue Lagoon back-to-nature frolicking of the back half and its emphasis on some kind of naturalistic fallacy of sexuality. It’s a thematic subtext that began to grow in me a feeling of discomfort, the idea that now they’re back in nature they’re pursuing a more ‘natural’ relationship. And it’s only when you start to parse out the film’s themes that you realise where the sense of discomfort comes from.

The writers have made many changes to the plot of the original novel on which the film is based. But they have kept the novel’s concern with the growing liberation movements of the 1960s. As we see in the original quote, the novel has a definite ‘kids these days’ vibe that suggests that no good can come from a society that’s too youth-focused.

As well as the growing influence of the younger generation, the writers of Logan’s Run seem also to agree with Huxley that there is something particularly dystopic about sexual freedom, especially the freedom of women to have sex without the threat of childbirth.

In an early scene where Jessica and Logan meet because she has put herself on the ‘circuit’ for a hook-up, she changes her mind and he asks her if she prefers women instead. In another scene, the two run through a kind of sex park where people engage in drug-fueled orgies and group sex. While initially reading as sex positive and accepting of homosexuality, you soon realise scenes like this are instead framed as part of the dystopia – evidence of it even. The Dome’s eventual liberation is not just a liberation from a short life or from a controlling technology. It’s the liberation of lifelong monogamy solely between men and women that will result in children.

It’s the so-called liberation of winding back the clock to 1952. One that whitewashes the normal variation in human sexuality out of existence.

While Logan has the lead role, it is Jessica’s growing devotion to Logan that is the show’s main emotional arc. Her declaration that she wants to be with him and only him culminates their escape from the Dome. Her decision to be a beloved wife to Logan’s beloved husband is the conclusion of the film’s character development. It’s not a stretch to say that their decision to be a monogamous heterosexual child-rearing couple is the main point of the film.

For science fiction, Logan’s Run is surprisingly regressive and, dare I say it, misogynistic and even homophobic. It predicts a sad and dystopic end for a society that allows women to have sex without children. And while it has other more interesting themes about faith and curiosity, dogma and knowledge, and the need for a society to retain its history, these are overwhelmed by its conservatism.

As a film, Logan’s Run definitely stands the test of time. But as a story, it should have stayed in 1976.

We have discussed at home whether it is time to watch Logan’s Run again. The last time would have been ten years ago where the boys cheekily said regarding the great Peter Ustinov – “dad, he looks just like you.”

So, I have watched Logan’s Run a number of times, including when it was first released. Dad was a great sci-fi fan and so it was off to the drive-in at a time. I remember being blown away and suitbly horrified as I worked out that I still had quite a few years up my sleave before having to go to the dreaded Carousel. However, for me, the endingWas was what made the movie memorable for me: that people can live to a ripe old age and have complete freedom to boot.

Each time I have watched it since, I have nodded my head and commented that, as a movie, it has stood the test of time. However, a TV series was made based on the film. It was terrible and I struggled to watch it on a regular basis. The book would have been better reference material. However, it was like all TV series at the time: location of the week and getting into trouble with the locals.

Getting back to the movie, Michael York as Logan 5 – what an amazing and mixed career he has had. Jenny Agutter did describe herself as perfect fantasy fodder back then and for a few years afterwards. I certainly have enjoyed when she has popped up in the many tv shows and movies since.

As for the story of Logan’s Run staying in 1976, I haven’t watched Zardoz for some time (it came out two years earlier), but after rewatching Just Cause the other night, I think I will track it down. Zardoz was generally panned by critics, but it is a very interesting film and commentary that sees Sean Connery in a very thought provoking role. John Boorman was a very visionary film maker. As some have said, he was either brilliant or terrible. No in between, it would seem.

I liked your review very much, Lee. Some of your other thoughts have got me thinking regarding its themes being overwhelmed by its conservatism. I am now going to have to watch Logan’s Run once more!