It was nearly five years ago that the first episode of the Korean romantic-comedy, I’m Not a Robot (INAR), aired. And Dramaland would never be the same. Or maybe the audience would never be the same. Or possibly just me. Either way, something changed.

Every now and then, somebody asks me if I have a blog post about the show. Instead, when INAR aired, my opinions in all their wild, unleashed glory, were scattered across the internet instead. Asking me to produce something coherent was almost impossible since I simply loved this show so much. I was an exuberant scattergun of joy and uncontrolled over-analysis.

Since INAR remains one of my favourite dramas, its upcoming five year anniversary seems like a good time for me to collate all my technicolour adoration into one place. This piece will deal mostly with the visual metaphors the show uses to tell its story; from Kim Min-kyu’s house of cards to Ji-a’s hearts.

None of this is new analysis. It’s instead a collation of things I wrote about the show’s amazing imagery and its deliberate and effective use of semiotics to tell its story. For a more complete analysis, you can’t go past Saya and Teriyaki’s wonderful recaps over on Dramabeans – truly some of the best recaps ever written. And of course, we recorded a deep dive podcast for Dramas Over Flowers.

And if you still haven’t seen I’m Not a Robot, then hopefully this inspires you to at least give it a try – with the simple, small caveat that nobody is saying this drama is perfect. It has its flaws. But you won’t find them in this post. This post is for everything the show did right.

A modern day fairytale

With its Beauty and the Beast* imagery, I’m Not a Robot is a gorgeous modern fairytale that also subverts the standard Chaebol/Candy romcom. Kim Min-kyu (Yoo Seung-ho) is the wealthy Chaebol in a stately mansion but also a cursed beast that needs to be saved from his isolation. Jo Ji-ah (Chae Soo-bin) is both hardworking, down-to-Earth Candy and a Warrior Queen in exile, fresh from slaying the dragon (or least acquiring limited edition figurines) and looking to prove herself.

They come into each other’s orbit because of scientist, Hong Baek-gyun (Uhm Ki-joon), who is Ji-ah’s ex-boyfriend. After their breakup, he creates a robot (well technically an android) version of her – Aji-3 – which rounds out our trio in this doppelgänger story. Aji-3 is programmed to be a perfect, subservient mechanism of docile femininity: created to reduce our Warrior Queen to something controllable.

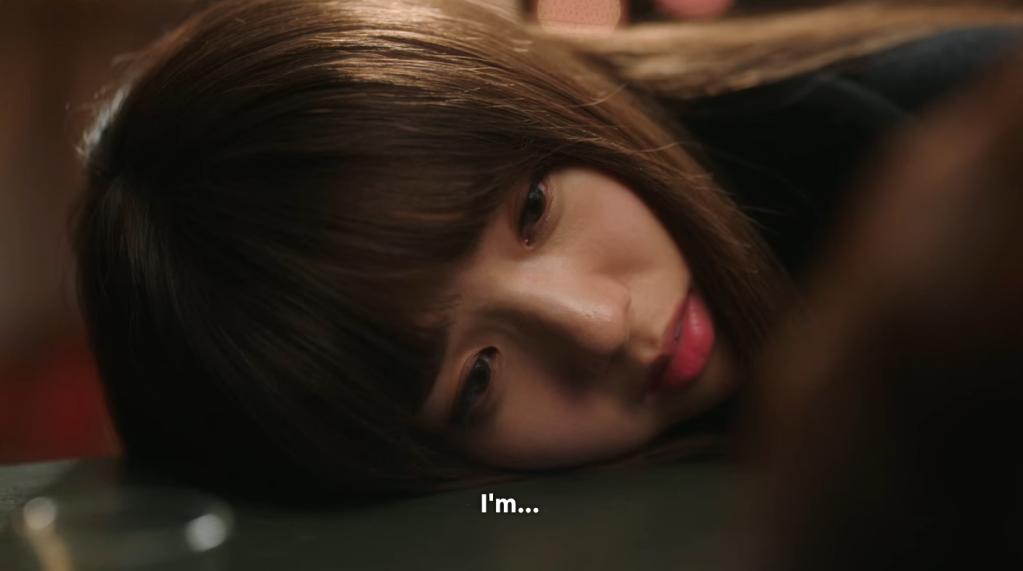

When Aji-3 breaks down right before Min-kyu is due to assess it as an investment, Baek-gyun pays the cash-strapped Ji-ah to impersonate it. But unlike Aji-3, Ji-ah is not a robot.

But before I launch into what I generously refer to as ‘my essays’, I’d like to take a moment to dwell on just how beautiful this drama is. Because it is. It’s stunning.

*I’m Not a Robot is also heavily influenced by the 1922 children’s book, The Velveteen Rabbit, written by Margery Williams and illustrated by William Nicholson. Since this post is concerned mostly with the show’s visual metaphors, it doesn’t include an analysis of The Velveteen Rabbit. But a post like that could exist. One day. That could happen.

A house of cards

Kim Min-kyu may be a rich second generation corporate heir, but he’s also an orphan who suffers from a unique affliction.

He’s allergic to humans.

As such he rattles around his giant mansion in permanent isolation, only venturing out if he can completely control his environment. His only friends are robots, all of whom he names ‘Pretty’ and for whom he even throws birthday parties. Using masks, gloves and a baton to fend off humans who come too close, he has a dangerous anaphylactic response to physical contact and is therefore utterly alone.

In the first episode of the series, Kim Min-kyu clambers up a stepladder to place a playing card on a giant house built of them in his main room. Later, Jo Ji-ah accidentally knocks this house down. It’s a moment played for laughs as part of her slapstick escapades while pretending to be Aji-3. And yet the entire scenario is intensely meaningful.

In later flashbacks, we see Min-kyu and his parents lay the foundation for the house of cards right before their deaths. Afterwards, he keeps building it, adding card after card. As he grows, so does the structure until it is a castle that mirrors the castle he lives in: the giant facade he puts between himself and the world.

In fact, it becomes so huge that it blocks out the sunlight. The room he lives in at the beginning of the show is dark. And yet he cannot dismantle it, just as he cannot leave the house he lives in. He dwells in shadow, both physically and metaphorically. Unable to let the light in, both physically and metaphorically.

When Jia arrives, she knocks down his house of cards. His first reaction is anger and loss. But he soon realises that the giant hall is now bathed in sunlight.

And that’s the entire show right there. His life is a house of cards. She will bring it crashing down. It will be painful but in the end he will come out of the darkness and finally live in the light. The Beast saved by Beauty. The trapped Prince rescued by his Warrior Queen.

Jo Ji-ah’s broken hearts

Throughout I’m Not a Robot, the imaginative and creative Ji-ah is trying desperately to gain some traction as an inventor. In this, Ji-ah is an extraordinary young woman: able to dream big and with the courage and drive to pursue those dreams. And she continues to, even when the whole world tells her to give up. Thrown out of her house by her controlling brother, she is cashless, homeless and dispirited but nonetheless undeterred. All she needs is just one person to believe in her and in her dream.

One of Ji-ah’s inventions is a set of connected hearts. When you touch one, the other lights up. It’s a simple image of love from a distance. If you split them between two people who are apart, all you have to do to send your love is to touch one. The other one will illuminate in an instant no matter where they are in the world.

The story of these hearts as they unfold in the drama is the story of Ji-ah herself. They represent not just her literal heart but also her inventions. To love Ji-ah is to love her brilliant, unconventional mind. Her heart and her work are inextricably linked.

Ji-ah invented her hearts while she was dating the much-older Hong Baek-gyun: a scientist and engineer who she mistakenly thought believed in her inventions but who merely patronised her. They were designed to represent two hearts in perfect sync. But Baek-gyun didn’t treat her hearts with respect, which led to the end of their relationship.

It took four years after the break up, but she finally got the hearts working again right before she met Min-kyu. She then submitted them to a competition run by his company and they saw the value in her hearts but Min-kyu shut the competition down. She then agreed to pose as Aji-3 in the hope that she could convince Min-kyu of the value of her hearts.

Her brother broke her hearts when he threw her out of his house. But then her ex-boyfriend finally recognised their worth and helped to repair them. With her hearts finally working again, she entered them into a competition where Min-kyu would judge their worth. Although they didn’t win, it didn’t matter because Min-kyu asked for her hearts anyway. He had both until he was finally ready to give her one.

This journey of Jia’s heart as both a literal and figurative representation of her quest to find somebody who understands and respects is portrayed throughout the drama as a subtle beat. Jia has her heart broken by both her brother and her boyfriend but manages to get it back in working order just in time to meet Min-yu. The one person who will finally respect it.

One of the most swoonworthy scenes in the drama is when Min-kyu pulls out one of Ji-ah’s inventions – an umbrella that can go transparent or opaque at will – and waxes lyrical about the genius that came up with the idea, unaware it’s one of hers. It’s no surprise that this is the moment Ji-ah truly falls for him. Her inventions are a part of her. Only someone who loves and respects them could love and respect her as well.

As I’m Not a Robot ends, she and Min-kyu both have one of her hearts. Connected across time and space no matter where they are.

I’m Not a Robot

Obviously the largest and most important visual metaphor is the character of Aji-3 herself. Aji-3 is a walking, talking objectified and commodified woman. A simulacrum of an adult human female who is nonetheless controllable, programmable, and obtainable. As long as you have enough money.

I’m Not a Robot is a wonderful, swoonworthy romcom with a lot of delightful and very funny scenes in it. But it has a darker and entirely serious throughline about the commodification of women. And since the show as a whole is deeply feminist then this subtle thread represented by the Aji-3 android becomes more powerful as the show unfolds.

The fact that Baek-hyun created his robot to look like a woman – but not just any woman, his ex-girlfriend who had the audacity to dump him – says a lot about him and his attitude toward women. Aji-3’s very existence represents a version of a woman that he can control. Dressed like a doll, programmed to be subservient and obedient, Aji-3 is a walking testament to a man who feels women need to be docile and, most importantly, governable. Her genius is also tightly controlled, limited to the memorisation and recitation of facts with no imaginative flair. An autistic male concept of intelligence. This Ji-ah would never leave him. She would never even know how.

Min-kyu’s desire to possess Aji-3 is similarly problematic. Because of his illness, he can only handle people and situations he can completely control. While Min-kyu’s situation is far more sympathetic because his illness results from deep childhood trauma, he nonetheless becomes obsessed with robots – and with Aji-3 – because he’s too scared a real human will hurt him. Min-kyu calls all his robots ‘Pretty’: an outstandingly sexist practice that reminds us that most AIs are given female voices. People are far more comfortable with a female voice in an efficient but hierarchically inferior role, like a competent housekeeper or secretary, than they are with a male voice in that role.

In line with the theme of men getting angry if they can’t control women, we also have Jo Ji-ah’s brother who tries to wield his financial advantage to force her to his will. The only time he’s seen to defend her is if he thinks her form is being appropriated by another man. Thus the only time he really acts like a brother is when he finds out that Aji-3 has been made in his sister’s image.

Aji-3’s plotline revolves around who controls her, who is able to touch her, who is able to give her orders and this has parallels with the way the other female characters are treated in the text.

But, unlike a lot of dramas with similar setups, I’m Not a Robot is not normalising nor condoning this framing. It doesn’t ask women to compromise to find love, nor does it come with a message that it’s women who need to be understanding of men’s attitude towards them and make allowances for it. Instead, the show demands the male characters change and grow to be worthy of the women in their lives. And while Ji-ah’s brother has limited character growth, Baek-hyun and Min-kyu work past their flaws. Baek-hyun in particular has the strongest growth as a character across the show’s run, learning to respect Ji-ah as the person she is rather than as the fantasy version he tried to recreate. And the fact that he does this without then being rewarded by them getting back together makes this arc even more powerful.

It says something that, to achieve her dreams, Ji-ah has to pretend to be a lobotomised doll who greets her owner with, “I love you, Master”. Of course Ji-ah instantly rebels against the strictures of this role; her natural personality breaking out. Ji-ah is not a robot. She is instead human in all her chaotic glory and as such struggles to find her place in a society that wants women to be perpetually unchallenging.

In fact, every single female character in I’m Not a Robot (of which there are laudably many) struggle throughout to assert their identity and to gain some agency over their lives. Self-determination in a society that’s stacked against you emerges as one of the main themes of the show as we contrast the living doll, Aji-3, with the real women in the text.

Aji-3 spends the show being quite literally bartered over but an important minor character is also Min-kyu’s childhood crush, Yi Ri-el. While Ji-ah herself spends the first half being forced to impersonate Aji-3 to be able to achieve her dreams. Ri-el is the “real” woman throughout the show. Her name even sounds like “real” in English. And yet she is fighting against the exact same oppression that Aji-3 is.

Near the end of I’m Not a Robot, Aji-3 is finally sold to an incredible Trump pastiche who informs her that, “you’re just a product owned by a man.” At the same time, Ri-el is being sold off in an arranged marriage that will benefit her father and his ownership of the company. She is owned as Aji-3 is owned. She is sold as Aji-3 is sold. She is a product owned by a man. The real human woman in this text is treated the same way as the literal robot, Aji-3.

When both Ri-el and Aji-3 rebel, it is a cathartic and joyful moment. Ri-el isn’t going to be told what to do with her life. Aji-3 escapes and goes home to Min-kyu. The other female leads are similarly striving for their own emancipation and self-determination, discovering who they are and what they want out of life without reference to other people’s expectations.

And while the writers somewhat undercut this with their decision to scrap Aji-3 in the final episodes, the message was nonetheless delivered.

I’m Not a Robot is available with full English subtitles on Netflix

For my mind, INAR is one of the best shows out there, and certainly the best of the AI type shows. It was clever, thought provoking on a number of levels, with very good performances and yes, I could relate to the need of taking time out from other humans 😂🤣😂

When I rewatched it in 2020 I realised it’s also a great pandemic watch. Min-kyu’s behaviour is even more sympathetic in a Covid era.

I’m just so glad this low-rated little watch got all the critical love it deserved – especially since no one watched it at the time!😂😂